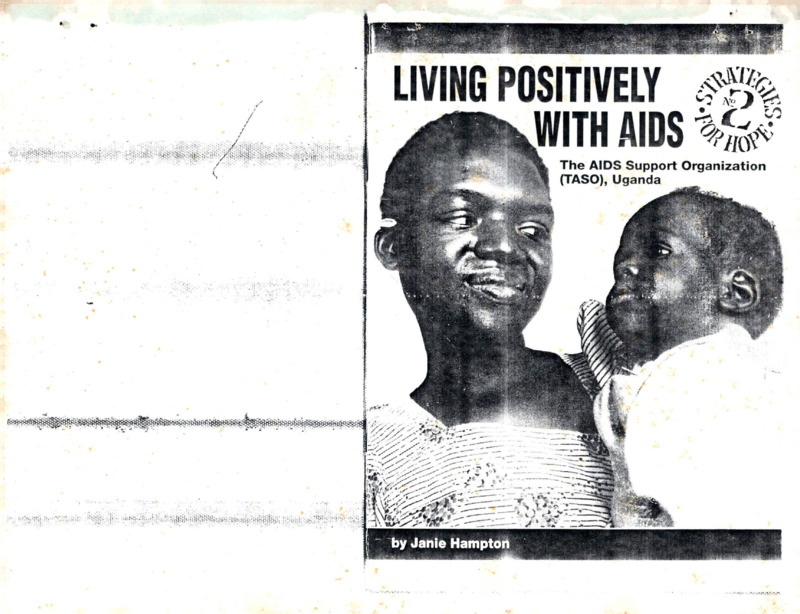

LIVING POSITIVELY .WITH AIDS

Item

- Title

-

LIVING POSITIVELY

.WITH AIDS - extracted text

-

LIVING POSITIVELY

.WITH AIDS

y-

pt"'

■■^41

AIDS Support Organization

w .! The

(TASO), Uganda

E

I z

•

V

v

LIVING POSITIVELY WITH AIDS

I

The AIDS Support Organization (TASO), Uganda

by Janie Hampton

I I

STRATEGIES FOR HOPE:

ActionAid

No. 2

REF

WORLD

IN NEED

Published by

ACTIONAID, Hamlyn House, Archway, London N19 5PS, U.K.,

in association with

AMREF, (African Medical and Research Foundation), Wilson Airport,

P.O. Box 30125. Nairobi, Kenya.

and

WORLD IN NEED, 42 Culver Street East, Colchester CO1 1LE, U.K.

©Janie Hampton and G & A Williams 1990

ISBN 1 872502 01 6

r

First edition 1990

Reprinted February 1990

Extracts from this book may be reproduced by non-profit organizations and

by magazines, journals and newspapers, with acknowledgement to the

author.

.-Si

a

The contents of this book have been reviewed and approved by the National

AIDS Control Programme of Uganda.

I

I:

I

1

LIVING

POSITIVELY

WITH AIDS

The AIDS Support

Organization (TASO), Uganda

CONTENTS

Introduction.........................

. . . 1

AIDS in Uganda

................

. . . 3

Origins of TASO................

. . . 4

Language ............................

. . . 5

......................

. . . 5

...............................

. . . 7

Staff ......................................

. . . 8

Medical care ......................

Children’s clinic ................

. . . 9

. . . .

. . .12

.........................

. . .14

Material assistance............

. . .17

Orphans...............................

. . .18

Training...............................

. . .19

Counselling the counsellors

. . .20

Funding...............................

. . .21

The future.........................

. . .23

Conclusion

......................

. . .25

Appendix: Training Courses

. . .26

Further reading................

. . .30

......................

. . .30

Order Form......................

. . .31

Organization

Clients

Hospital admissions

Home care

*

Photographs: Carlos Guarita

Cover and design: Alan Hughes and Brendan McGrath

Typesetting: Wendy Slack and Kate Stott

Illustrations: Clive Offley

Printed by Parchment Ltd, Oxford, U.K.

References

Edited and produced by G & A Williams, Oxford, U K

1

■J

. . .11

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

i

no to the clients, counsellors and medical workers of

TA^Tfor giving their time, knowledge and friendship to the author

wnite researching this book.

MMM

most grateful to Dr Sam Okware, Director of the

We a-e also

AIDS Control Programme, for his support and encourageUgandan

meat.

Organization's Global Programmme on AIDS has

P'ovX generous assistance to make this book as widely available

as possible-

NOTE

Tbe names of

TASO clients mentioned in this book have been

changed.

'*■ I

3

Keeping busy is part of living positively.

Introduction

The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) is

the first organized community response to

the AIDS epidemic in Uganda. Founded by

a group of volunteers in late 1987, TASO

now provides over 2,000 people with HIV

or AIDS, and their families, with counsel

ling, information, medical and nursing care,

and material assistance.

Most TASO workers are themselves

people with HIV or AIDS. They know that

they may not have long to live. Yet TASO

is not pervaded by gloom and despair. On

the contrary, it is an organization in which

there is an amazing amount of laughter,

good humour, and infectious enthusiasm.

There is always a sympathetic ear to listen

to personal problems and a shoulder to

weep on if necessary. But TASO’s workers

have an overwhelmingly positive approach

to life. They embody the organization’s

commitment to ‘living positively with

AIDS’.

This book is about that commitment, and

how it can be translated into practical action

in the face of the prejudice, discrimination

and fear that have been generated by the

threat of AIDS.

Positive Living

TASO’s slogan is ‘Positive Living with AIDS'. In practical terms

this means:

* Not blaming anyone.

* Not feeling guilty or ashamed.

* Having a positive attitude towards oneself and others.

* Following medical advice by:

- Seeking medical care quickly when infections such as bronchitis,

thrush and skin sores appear. Every time a person with AIDS gets an

infection, the body’s resistance to AIDS is further lowered.

- Not smoking or drinking alcohol, which lower the body's resist

ance to disease.

- Eating plenty of food which is rich in proteins, vitamins and carbo

hydrates.

- Getting enough sleep and not getting overtired.

* Taking enough exercise to keep fit (but no strenuous exercise).

* Continuing to work, if possible.

* Occupying oneself with non-stressful activities such as crafts.

* Receiving both physical and emotional affection.

* Socialising with friends.

* Receiving counselling to maintain a positive attitude and talk

about feelings, whether angry, sad. blaming or hopeful.

* Always using a condom during sex, even if both partners know

they are HIV-positive, in order to prevent pregnancy and avoid catch

ing any other sexually transmitted diseases, which would further

lower immunity to disease.

* Avoiding pregnancy because it lowers the body's immunity and

can hasten the onset of AIDS in an HIV-positive woman.

infection are increasing.

aids in Uganda

The first cases of acquired immune

AIDS is an expensive disease. The

deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Uganda medicines are costly, and patients are un

were reported in Rakai District, to the west able to work but need more food. Many

of Lake Victoria, in 1982. Since then the Ugandans with AIDS never get to an AIDS

number of cases reported each month clinic because they are too poor or too weak

nationwide has doubled every six months. to travel and wait in a long hospital queue.

By December 1988 over 5,000 cases had Better-off patients tend to live longer and

been reported to the national AIDS Control enjoy a better quality of life because they

Programme, but these are only a small can afford to buy nutritious food and to pay

for medical care and drugs.

fraction of the total.

For the people of

The number of

Uganda, AIDS is part

people infected with

SUDAN

of a cumulative

human immunodefi

catastrophe. The

ciency virus (HIV) country’s economy

the virus which

and social infrastruc

causes AIDS - is

ture are only just be

many times greater

ginning to recover

!<

than the number of

from nearly 20 trau

AIDS cases. Surveys

UGANDA

matic years of civil

in some urban areas

war and unrest. The

of Uganda have ZAIRE

damage has been

found 15-25% of

enormous and re

people in the sexually

covery is painfully

active age group to be

j

infected.2 At the

Hospitals and

KamPa,aX^^yKENYA slow.

health centres are

Mulago Hospital in

Masaka •

run-down, and essen

Kampala, the pretial drugs and equip

|i T&p valence of HIV infecment in short supply

tion among patients

J

Lake

or non-existent.

admitted for medical

Victoria

Many health profes

f ; y treatment increased RWANDA

sionals have either

A from 10% in late

left the country or

1986 to 50% two

■ o i|

TANZANIA

taken other jobs be

|j

years later.’

In Uganda, as

cause their salaries

elsewhere in Africa, transmission of HIV is were so low. There are, for example, only

I

I

iK

mainly through heterosexual intercourse five doctors for every 100,000 people.

I.

and from mother to unborn child. Men and

The Ugandan health services, on their

■

. women are affected in equal numbers. own, cannot possibly cope with the rapidly

■ i’.

AIDS in Uganda affects all members of the escalating numbers of people with AIDS

family - either directly or indirectly. (In who need medical and nursing care, as well

,

the industrialized world, by contrast, as social, psychological, and material sup

-!1 i

:

/AIDS affects mainly single people.) The port. Government services need to join

age of first being diagnosed HIV-positive forces with community organizations in

I

ranges from around 18 to 30 years for caring for people with AIDS and their

.1 women and from 17 to 37 years for men. families. That is why the emergence of an

.^p The numbers of children bom with HIV organization such as TASO is so important.

'1

i

6

iJ j

■

■4

;

________

!■

-

i

>.■

3

at

Origins of TASO

TASO has its origins in a small group of

people who began meeting in one anothers’

homes in Kampala in October 1986. The

group consisted of a truck driver, two sol

diers, a veterinarian’s assistant, an office

boy, an accountant, a physiotherapist, a

nurse, a school teacher, and a social

scientist. All but one had HIV or AIDS.

They met to exchange information, to give

one another support and encouragement,

and to pray.

In January 1987 one member of the

group. Chris Kaleeba, died. His wife

Noerine (see panel) was devastated:

“I just went to pieces. I knew that Chris

Noerine Kaleeba

Director of TASO

In June 1986 Noerine Kaleeba’s hus

band, Chris, was taken critically ill while

studying at Hull University in England. 11 •

“The British Council brought me to be

with Chris while he

was in hospital for

four months. He was

the first Al DS patient

at

Castle . Hill

Hospital, and the

staff were marvel

lous, so kind and

compassionate. I

met the ‘buddy’

group* in Hull and

for three weeks

Chris, our ‘buddy’ and I talked of nothing

else. It was easier for us because we

realized that Chris must have contracted

HIV from a blood transfusion after a bus

accident in 1983. But whatever the exact

cause of HIV transmission, it’s the effect

that has to be dealt with. There’s nothing

to be gained from blaming one another or

feeling guilty.

hris wanted to come home to die,

so in October 1986 he arrived at Entebbe

airport to be greeted by a crowd of family

and friends. Most were well-wishers, but

some had come only to see what he

looked like. He was just strong enough to

walk out of the plane.

“We tried all the herbal medicines we

could find for three weeks. He drank them

.

by the jerry-can full! We never tried witch

craft, which some people suggested.

Finally he said: ‘Enough, we aren’t

achieving anything. I'm drinking so much

herbal medicine that

I have no appetite

for food. I must eat

good food. Let’s

plan what to do

when I go.’

“There really

wasn't much sup

port here in Uganda,

except from both

sides of the family.

But even they didn’t

fully understand what was happening.

They could give emotional support but we

were short of medicines and material

support. There was stigmatization from

friends and neighbours.

“The idea of TASO originated from the

example of the doctors and nurses who

looked after Chris in Britain - the kind

ness and care they showed him, despite

the fact that he was a foreigner and had

5.IDS. We were also impressed by what

we had seen in Britain of the Terrence

Higgins Trust and the ‘buddy’ system of

counselling.

“My Christian faith was strengthened

by this experience. Though there have

been many times when I have said ‘Why

me, God?”’

•Volunteers who provide support and counselling to people with HIV/AIDS.

4

was going to die, but when it happened it

was just too much. I took my children and

left Kampala to go and stay with my

parents.”

Three months later, when she returned

to Kampala. Noerine Kaleeba was deter

mined to do something practical to help

people with AIDS and their families. The

group which she and Chris had helped to

start began meeting once more, and a few

new members joined. When TASO was

formally established in November 1987, the

group consisted of seventeen people,

including twelve who had HIV or AIDS (all

of whom have since died).

The founding members of TASO had no

training in counselling or experience of

managing an AIDS support group. There

were no precedents for such groups in

Africa from which they could learn. They

had no office, no transport and no funds. But

what they did have was initiative, vision

and a deep commitment to practical action

on behalf of people with HIV and AIDS,

who were being neglected by the health

services and ostracized by the rest of

society. It was this combination which

persuaded two British organizations ActionAid and World in Need - to provide

TASO with the funds to get started.

ActionAid also arranged for two found

ing members of TASO to participate in a

one-week training course for AIDS

counsellors in London.

All those involved in starting TASO

were practising Christians who regularly

prayed together, but they made a conscious

decision to make TASO a non-religious

organization:

“We want to be open to everyone,” says

founding Director Noerine Kaleeba.

“Everyone should feel equally at home in

TASO.”

Although TASO is a non-governmental

organization, another key factor in its estab

lishment was the open and constructive

attitude of the Ugandan Government.

“One cannot rely on government fund

ing, but the government’s blessing is

necessary," says Noerine Kaleeba. “We

have been very fortunate. Uganda's

National AIDS Control Programme is run

by creative and adaptable people, with a

helpful attitude."

Language

At TASO the word ‘AIDS’ is rarely used.

People with HIV or AIDS are described as

being ‘body positive’. They are referred to

as ‘clients’, never as ‘AIDS victims' or

‘AIDS sufferers’. The term ‘patient’ is used

only if a client is admitted to hospital.

TASO is also sensitive to words like

‘catastrophe’, ‘plague’, and press state

ments such as ‘This person is going to die'.

“We are all going to die sometime, so

why pick on a few of us?” said one TASO

client. “I have already lived longer than my

father, who died of malaria.”

Some TASO clients are also annoyed by

government slogans such as ‘1 said NO to

AIDS’:

“No one has ever said ‘Yes to AIDS’.'

says Susie, a TASO client and counsellor.

“None of us have asked for it. Most of us

who have it now had never even heard of it

when we caught it. You cannot attach blame

or assign guilt to anyone. It doesn’t matter

who was responsible - the husband or the

wife or the blood transfusion. The import

ant thing is to think and live positively.”

Organization

TASO has two offices-one in Kampala and

the other in Masaka, 80 miles to the south

west. These are open from Monday to

Friday and clients can come without an

appointment. Most counsellors, however,

work only part-time for TASO, so clients

make an appointment if they want to see a

particular counsellor. A file is kept on every

client, with details of hospital admissions,

medical treatment, material support, visits,

and family conditions. Clients are allowed

to read their own files.

TASO Kampala’s office is a modest.

5

Clients

TASO's clients are people with HIV or

AIDS, and their families. In March 1989

there were 140 adult clients registered with

TASO Kampala and 85 with TASO

Masaka. Some male'clients may have

wives and families living in distant rural

areas who may also be infected with HIV.

but are not registered with TASO.

'ij r fl

TASO Kampala works within ten miles

of the city centre, so their clients are urban

and mostly of middle or low socio

economic status. Most are referred to TASO

by the two AIDS clinics at Mulago

Hospital, and some by other hospitals or

private clinics.

TASO Masaka’s clients are mostly

rural, subsistence farmers referred from the

Eddie

TASO client and counsellor

Tea and friendship are always available at the TASO day centre.

unmarked room in Mulago Hospital, a col

lection of run-down buildings near the

centre of the city. A separate building,

known as the ‘development unit’, is used as

a training centre and a meeting place. Also

in the hospital grounds is a day centre where

TASO clients and their families can meet.

People come together at the centre to make

friends, share information and express their

feelings in a safe, friendly atmosphere.

Lune! . provided every day for clients,

visitors, and any TASO workers who hap

pen to be present. Taking meals together is

an imponant part of demonstrating that HIV

is not transmitted by sharing cups, plates

and other eating utensils. Every Friday, all

6

TASO workers come to the day centre to

share a meal with co-workers and clients,

and to exchange ideas and discuss

problems.

The day centre is also equipped with

four treadle sewing machines which clients

use to make clothes and sheets for sale. One

client, a talented artist, makes batik hang

ings which are sold to benefit both the client

and TASO.

Places for rest are available for anyone

who feels tired and needs to lie down for a

short while. Young children are always

welcome: their numbers are greatest on

Fridays, when the AIDS clinic for children

held at the hospital.

Eddie is 37, an economics graduate of

Makerere University, Kampala. In 1981

he and his wife went to Nairobi for further

studies, returning in 1985. A year later his

wife had a recurrent

fever.

‘The fevers sub

sided fora while, but

she kept swelling in

different parts of her

body. She was ad

mitted to hospital in

Kampala

with

typhoid. Soon after

she came out of hos

pital, still weak, I

visited a friend who told me about AIDS.

The friend suggested that I should be

tested for AIDS. I was found to be HIV

positive.

“I had never heard of AIDS or HIV

before, and I didn’t know what to do.

When I went to the doctor for the results,

I couldn’t believe it. He just said, ‘Well

there you are, you're positive. You’ve got

AIDS, so there is nothing I can do. Too

bad.’ I felt like committing suicide.

“I came home after several hours and

during supper I told my wife about the

test. After that we cried together. Then

she was tested and we found out she had

it too. Her relatives wanted to take her to

a traditional healer, but we couldn't tell

them the truth.

“I was with her all through from the

start to the finish. She died a few months

ago, at home. I’ve now lost a lot of weight

and my skin is often septic with sores. I

am too tired to work. At first I didn’t want

anyone to know that

we had this disease.

I even worried about

being seen going to

the clinic. Then I met

two friends there

and we talked about

it together. Now I

don’t care who

knows. I feel that my

experience might

help others in show

ing them that hiding is no use.

“The children are my main worry.

They are nine, five, and three years old

now. The young one is always sick, she

has a fever and diarrhoea a lot. I’m sure

she has AIDS too, but I can’t bear to get

her tested. We are very close to each

other. I know now that I will die before I

can bring them up, so what will happen

to them then?

“I often wonder who brought the dis

ease into the family. I lie awake at night

wondering, which of us is to blame? It

might have been either of us I suppose.

But now I have joined TASO I am trying

not to blame anyone, myself or her. OK,

I have the disease, but I am going to use

my skills and experience to help other

people before the disease gets me.”

7

5

AIDS clinic at Masaka Hospital. Some

clients come straight to the TASO office

after hearing about the organization from

friends, and TASO then refers them to the

AIDS clinic in the local government

hospital for diagnosis.

Some clients want TASO to take over

responsibility for everything - finances,

food and housing, as well as emotional

stress. TASO does not have the resources to

do this, and in any case does not want to

become simply a ‘hand-out’ organization.

"The main objective,” says TASO

Director Noerine Kaleeba, “is to help

people to come together and discuss things

and feel accepted. The sense of belonging

restores their dignity. It’s much better if

they can come out and have some activities

and friends. Otherwise quite a few would

just give up.”

But not everyone who is offered coun

selling and other support from TASO takes

up the offer. AIDS carries a powerful stig

ma. fuel led by fear and ignorance, and some

people are afraid that TASO will tell their

employers, or that their workmates or

neighbours may learn that they are HIV

positive. Others fear they will be asked too

many questions, or be blamed for contract

ing the disease. Some try to deny they have

AIDS by moving house and changing their

jobs, or even their names. (They may then

continue to spread the virus through sexual

activity.) Others reject the offer of counsel

line and medical care in the belief that it

cannot help them. Some believe they have

been bewitched or have not observed the

correct rituals, and so seek treatment from

'witch doctors’ or traditional healers. Many

ignore the problem until they are too ill to

make plans for their families.

Confidentiality is of prime importance

to all TASO clients. There is no sign outside

the TASO office, and only one of the orga

nization's four vehicles is identified as

belonging to TASO. Several clients have

s|K'cifically asked that this vehicle should

not c ie near their homes. Some clients are

able to ork through the initial fear of being

8

identified as a person with HIV or AIDS.

Others, however, risk losing their jobs and

homes, or being rejected by their spouses.

Noerine Kaleeba is well-known in

Kampala as the Director of TASO, so she

reassures new clients and counsellors that,

for their own privacy, she will not greet

them in public places:

“Everyone knows what I do, so if some

one sees me giving you a hug, they may start

spreading rumours.”

Fred

TASO client and office messenger

Fred is 26 and was a taxi driver. He is

married with four children.

“I started to get severe fevers and was

admitted to hospital

for a week. Event

ually I was too weak

to drive any more. I

suspected I might

have AIDS, but I was

afraid to find out.

Then I came to

TASO and they

counselled

me

about the test. So I

wasn’t so afraid to

have my blood taken. When I found out I

had the virus, they were very good to me.

Staff

TASO Kampala employs seven full-time

staff and 17 part-time counsellors, trainers

and advisors. The full-timers consist of the

Director (Noerine Kaleeba), an accountant,

a publicity officer, an administrator, a sec

retary, a driver, and a cook/cleaner. The

part-time workers consist of a medical

adviser, three counsellor/trainers, 12 coun

sellors and an honorary legal adviser.

TASO Masaka employs a part-time

medical adviser and a full-time office mess

enger. The 12 part-time counsellors in

Masaka include two nurses, a social worker,

a medical assistant, a school teacher, and

several unemployed people with HIV or

AIDS.

TASO follows a policy of actively

recruiting people who are HIV-positive,

especially as counsellors. Many first come

into contact with TASO as clients and then

decide to become actively involved in the

.. .1 more

organization., They

falloften

ill than

healthy people and several have died since

starting work with TASO. This causes a

lack of continuity in TASO’s work, but

Noerine Kaleeba believes that the advan

tages of employing people with HIV far

outweigh the disadvantages:

“People with AIDS are a special asset to

TASO as counsellors. They are closer to the

clients and make them feel more normal.

They can talk from personal experience of

the emotions and problems caused by

AIDS, and can help people overcome

them.”

I

I

4

Counsellors have about ten clients each,

whom they visit at home once every week

or fortnight. A counsellor remains with the

same client from the diagnosis of HIV in

fection until death. Even when a client has

died, the counsellor remains in touch with

the family, which may contain other people

with AIDS or orphaned children.

Counsellors are accountable to their clients,

but also report to the TASO doctors, their

supervisors, and the office administration.

All counsellors first have to complete a

four-day induction course run by TASO’s

own training staff (see Appendix). They are

paid 1,200 Ugandan shillings (US$4.80) a

day, and also receive a free lunch and trans

port to their clients’ homes. Counsellors

who are HIV-positive continue to receive

material support such as eggs and school

fees for their children.

Once a week all counsellors meet for a

whole afternoon to discuss the progress of

their clients as well as their own problems.

The stress of working with terminally ill

Then they employed me as the TASO

office messenger. My mother had ten

children. I’ve lost two brothers to this

disease, butthey did

not have any sup

port. They left seven

children between

them. Two more of

us are HIV-positive

and we have 16

children between

us. I haven’t enough

money to make sure

my children will be

OK. There is nothing

left to sell. My mother always cries when

she sees how thin I’m getting.”

patients can lead to conflicts requiring

quick resolution.

Medical care

Medication is provided free to clients under

medical supervision, as long as supplies (or

funds to purchase them) are available. The

drugs are given out at the TASO office, at

the AIDS clinics in hospital, and on home

visits. TASO receives some drugs as dona

tions and purchases others locally.

Drug supplies, however, are far from

adequate. In 1988, for example, TASO

budgeted $5,000 for expenditure on all

drugs, but eventually had to spend $8,000

on supplies of a single product, Nizoral (for

the treatment of oral thrush), which cost 500

Uganda shillings (US$2) per tablet on the

open market.

Some TASO clients have reported relief

from certain AIDS symptoms after taking

herbal medicines, but these have not yet

been tested scientifically. Research on

9

0

ceric:'

now

?ieparanon''. however.

IS

branches lune a

5 Alic a token sum ot

ad\ ’-eShL;.- z LS5> a month for attending

re to three morning" a vv eek.

TASC i

_ _____ TASO client nee<K urgent

and v-e-estr

mediJi. >r.en:.<'r.. Tbev aFo run xepmak

HIX i:____ for adult" and children

once i -oe». r hospital, seeing up to 45

pal lem

D- E... Krabira. who t" the medical

adv is-; TASO Kampala. aFo work" as a

phvsir^r. a: Mulago Hospital and as a

Lecicrer ir. Medicine at

Lniv—srv. Wren he fuM "Ct up an A >

clinic a Mui^o Hospital in late

manv of his colleagues were sceptical:

“Health workers knew there was no cure

for AIDS, so they assumed that people with

AIDS didn't warrant any medical care. We

started the AIDS clinic to show what could

Ih' done. We had to demonstrate to patients

and health workers alike that people with

AIDS who come in very sick can leave the

hospital walking.”

Dr Katabira's AIDS clinic has been

inundated with patients. By February' 1989

he had seen a total of 850 adult patients 55' < men and 45% women. The most com

mon sv inploms were weight loss, recurrent

fevers and diarrhoea.

Dr Sam Kalibala is the medical adviser

to TASO Masaka. Since his HIV/AIDS

50:^:: v

Dr Elly Kat^Tpnescribes

for . mother and her HIV-positive child.

clinic opened in November 1988, the

number of new clients has doubled every

week. Working with TASO has changed his

approach to treating people with

HIV/AIDS:

“I used to see people with AIDS, but

before coming into contact with TASO I

didn't know what to do. I didn't know what

to tell them because I felt I couldn’t do much

for them. So we were hiding the diagnosis.

It was too painful to tell them. But when I

heard about positive living with AIDS, I

saw there was something that could be done

- for example, by counselling people before

and after the HIV test.''

Patients are usually referred to an AIDS

clinic on the basis of their clinical history.

The doctor at the clinic takes the patient’s

history and either makes a clinical diagnosis

or offers the patient an HIV test. If the

patient agrees to undergo the test - and

providing HIV test kits are available at the

time - a blood sample is taken. The result is

usually available a week later. If the test is

negative, a TASO counsellor explains how

the patient can avoid becoming infected

with HIV. If the patient asks for condoms

the counsellor provides some free of charge

and also explains how to use them correctly.

If the result is positive, the doctor

explains the implications to the patient:

“When I make an AIDS diagnosis,” says

Dr Katabira, “I have to tell the patient that

there is no cure for the virus, but there is a

lot that can be done to treat the infections

that may come along as a result of HIV

infection. The period from HIV infection to

death is usually less than two years, but it

may be up to five years.”

TASO counsellors are also on hand at

the clinic to offer clients counselling and

other support. Often, however, the clinics

are packed and if only one or two counsel

lors are on hand it is impossible to meet and

talk with all potential clients. At the time of

the initial diagnosis clients are usually in

such a state of shock that in-depth counsel

ling is not possible. Counsellors concen

trate on reassuring them that they are not

__ L

about to die, and arrange to visit them at

home within the next week.

Children’s clinic

An AIDS clinic for children is held every

Friday morning at Mulago hospital in

Kampala. Over 140 children with

HIV/AIDS are registered with the clinic,

and more than 30 are brought for diagnosis

or treatment every week.

Most of the children are babies or tod

dlers. Babies infected with HIV develop

AIDS more quickly than adults. Few sur

vive beyond the age of two years, and many

die before being diagnosed as having AIDS.

Most die within a year of birth, often of

dehydration or malnutrition due to repeated

diarrhoea and other infections. Many are

not brought to the AIDS clinic until they are

already close to death.

TASO counsellors talk with mothers as

they sit on a low wall, suckling their babies

before seeing the doctor. The nurse calls the

mothers into a small room where Doctor

Laura Guay sits close to them, clicking and

smiling at the babies. She asks the mother

how the baby is this week and examines the

baby gently, feeling for swollen lymph

nodes, listening to the chest, and looking in

the mouth for thrush. Many babies require

ampicillin for chest infections, others are

given oral rehydration salts for diarrhoea.

Whenever the drugs run out TASO provides

whatever it can until the hospital’s supplies

are replenished.

Blood tests are usually necessary to

diagnose HIV infection in babies and young

children because the symptoms of AIDS in

young children are similar to many other

children's diseases. But taking blood often

involves a struggle. Doctors and nurses may

have to take blood without the protection of

rubber gloves simply because there are not

enough gloves available. Inevitably, blood

is spilt from time to time. Dr Katabira insists

that the safety risk is negligible:

“It's quite safe as long as you wash your

hands well with soap and water afterwards.

11

I

LIBRA PV

(

>

AND

DOCUMcNTATinM

li

5

Susie

TASO client and counsellor

Susie, 24, took ’O’ Levels at school

and then got married. By 1986 she had

two children. Her third child died a few

days after a premature birth. During her

fourth pregnancy

she was sick a lot.

The baby was born

at full term but

became sick after a

week. Susie was

also ill and they were

both admitted to

hospital. Sickle cell

disease was diag

nosed shortly before

the baby died. Susie

recovered but was then readmitted to

. hospital with typhoid.

“When I found I was HIV-positive, I

did not know what to do. My neighbour

got AIDS and she tried to kill herself and

her children. I too felt like taking poison.

I looked so ill. I couldn’t walk or do any

thing. Then I heard about TASO and

since then everything has changed. I feel

much better now. When I am sick they

support me and are kind. They give me

medicines and some food. The counsel

lors never neglect you, they support you

through everything. My children are my

main worry, the school fees are so high.

I am hoping that TASO can help with

that. My relatives could look after them,

but they need help with food and school

fees.

“My husband has gone now, I don’t

The main danger of infection is not from

HIV but from diseases such as TB, hepatitis

or typhoid.”

All the mothers of babies and young

children with AIDS are themselves HIV

positive. They may discover this only when

their babies are diagnosed.

12

know where. When he knew that both my

co-wife and I had AIDS, he just went. He

must have it too. I still live together with

my co-wife and her children. She has two

children alive. Three

others died.

“Up to now, my

parents don’t know.

I will go and tell them

myself soon. I don’t

want them to find out

from someone else,

but I have to be

strong enough to

cope for them as

well as for myself.

They have paid out so much forme, but

now they will get nothing back. I cannot

help them in their old age. The people we

share a house with wouldn’t let us live

there if they knew. They have said in front

of us ‘If anyone had AIDS, we would

throw them out’. So we can’t tell them, but

they will suspect eventually. I hope that

TASO will helpihem to realise that it is

not a threat. We are suffering more from

this disease because of people’s ignor

ance. It is bad enough without ignorance

as well. But we have to fight the virus, so

we can live longer."

Susie attends the day centre most

days, but sometimes she is too weak to

work as a counsellor. She has been

coughing for three months and frequently

has diarrhoea and vomiting with

headaches.

able. Surgery, however, is used only very

sparingly because of the risk of precipit

ating AIDS in a person with HIV infection

by further weakening the body's immune

system.

Mulago Hospital does not systemati

cally test in-patients for HIV infection.

However desirable it might be to do so.

there are simply not enough AIDS testing

kits available. Diagnosis is usually done on

the basis of a physical examination. Many

hospital patients are admitted, treated and

discharged without the staff knowing that

they are infected with HIV. Nurses are not

issued with gloves for general nursing care,

but are taught to be careful and to wash their

hands thoroughly after contact with

patients.

The hospital does not have a special

AIDS ward. Dr Katabira believes that such

a ward is not justifiable and could lead to

other problems:

“A special AIDS ward would increase

the stigmatization of people with AIDS.

*«a

Hospital admissions

People with AIDS are admitted to hospital

whenever they require in-patient treatment,

which is given free of charge. Severe dehy

dration after diarrhoea or vomiting is the

most common reason for admission. Most

diseases associated with AIDS are treat-

Noenne Kaleeba counsels a mother at the children’s clinic.

13

0

A Hospital Visit

Sally lies in her bed in the passage of the

mixed medical ward. She has no sheets

and the mattress is stained and worn. A

thin blanket covers her emaciated body.

Most of the other patients have a relative

sleeping under the bed, their cooking

pots and blankets piled around them.

Sally has no-one. Her relatives simply

brought her to hospital and left her.

Mary, a TASO counsellor, brings her

eggs and some anti-lice shampoo.

“These mattresses are full of insects,”

she explains.

Sally receives free medical care, but

TASO has to pay a hospital orderly to

make up a flask of tea every morning and

wash her. She can barely raise her head

to sip the tea.

“We used to see a lot more like her,”

says Mary, “but now relatives are learn

ing that there is no danger in caring for

people with AIDS. Many relatives are a

lot more caring than some health

workers.”

In the next ward lies Rejoice, aged 18.

As Mary approaches she tugs her blouse

over her bare chest, but there is nothing

to hide. Her ribs stick out through the

sagging skin and her breasts have with

ered away, leaving just flat nipples. She

can’t sit up, but smiies with pleasure to

see Mary. Rejoice’s mother takes the bag

of eggs, milk powder and soap. She has

already lost one daughter to AIDS, and

These patients are no more of a risk in a

general ward than other patients. We be

lieve that all patients should be nursed and

managed in the same way, as if they were

all HIV-positive.”

In any case the problem of AIDS is

already too enormous to be dealt with by

separating AIDS patients into a single hos

pital ward. In Kampala alone it would be

necessary to allocate up to half of all hospi

tal wards to AIDS patients, and there are no

14

has been with Rejoice ever since she was

admitted to hospital. Rejoice’s 12 yearG.d brother comes in smiling, carrying the

day’s shopping and clean bedding. He

will sit and read to his sister while their

mother takes the bedding home to wash.

The children’s ward smells strongly of

urine and the noise is deafening. The

mothers are lining up with their babies

and children for injections. Some are so

thin there is barely enough flesh for a

needle to penetrate. By the window lies

Karen, aged 14 months, a tiny body in a

large metal cot. Karen is dying of AIDS.

She weighs a mere 6.5 kilos - the weight

of a normal 3 month-old baby. Her

mother sits beside her, their belongings

under the bed. Six weeks ago Karen was

well and just beginning to walk. Then she

had a fever, diarrhoea and vomiting. Now

she can’t even sit up, let alone crawl. A

tube is taped across her face, leading into

her nose and down to her stomach.

Karen’s mother expresses breastmilk

into a cup and feeds her through the tube.

Karen’s mother knows that she must

be HIV-positive too, though she is not yet

ill. She is already concerned about the

future for her other two children after she

dies. Mary reassures her that she is not

going to die soon, but TASO will help with

the other children if the need arises in the

future, as long as the children can stay

with relatives.

valid medical grounds fordoing this.

“Every AIDS patient," says Dr Katabira,

“is admitted with a different problem. They

cannot all be lumped together."

Home care

TASO counsellors try to visit clients once a

week at home, unless clients prefer to come

to the TASO office. Counselling is done in

the local language whenever possible.

I

TASO counsellors spend a great deal of

time listening to clients and their families

talk about their problems. Rather than pre

scribing solutions, they aim to provide their

clients with information about how they can

look after themselves and lead positive

lives. Noerine Kaleeba is convinced that

this approach is effective:

“People with HIV can live positively by

gaining morale, rather than giving up. They

can choose to eat good nutritious foods, and

not to smoke or drink alcohol. They can get

I

7',=

*

i

I

immediate medical care for every infection.

Through positive living, people with HIV

can make the most of their remaining time

and even extend it."

Home care has many advantages over

hospital care. It enables the counsellor to

assess the client’s social and economic

situation. It also helps to break down or

prevent the sense of isolation experienced

by many people with HIV and AIDS. Home

care also brings the counsellor into contact

with other members of the client's family.

Home Visits (morning)

Godfrey’s first home visit of the day takes

him to a township on the outskirts of

Kampala. The TASO vehicle stops under

a banana tree. Godfrey and the driver,

Sam, climb out and walk past a patch of

sweet potatoes to Sandra’s house. There

.are six outside doors, each one leading

/ into a dark, windowless room with an

earth floor and bare mud walls.

Sandra appears from behind the

house, where she has been tending the

cooking fire. She is tall and very thin. Her

face is so wizened she could be any age.

Her prominent cheekbones emphasize

the depth of her eyesockets. She has

only one child, four year-old Rosie.

After the formal greetings, Sam sits

under a tree and plays with Rosie and her

cousins, while Godfrey goes inside the

house with Sandra. She shares a room

with Rosie and a young niece. There are

22 members of this extended family,

ranging from a six day-old baby to two

grandmothers in their seventies. Godfrey

gives Sandra eggs, milk powder and a

bag of clothes for Rosie.

Sandra and Rosie were living in a

rural area until they were called to

Kampala because her husband was sick.

By the time they arrived, he had died .of

‘unknown causes’. Soon afterwards

Sandra fell sick, and was too weak to go

back home. By this time the family sus-

pected that her husband had died of

AIDS. Afraid that they would catch it too,

they isolated Sandra. She had to stay in

one room, with her food left at the door.

No-one spoke to her. She lay on the floor,

with diarrhoea, vomiting and headaches.

One day she was so bad that her relatives

carried her to the main road and took her

by bus to the hospital. She was admitted

and the doctor diagnosed HIV infection.

A week later, when she was feeling much

better, she learned about TASO through

Godfrey, who had been appointed her

counsellor. He realised that his first task

was to counsel the family and show them

that there was no risk to themselves. As

a result, Sandra now shares their food,

and sits and talks with them. Now that she

receives medical treatment as soon as

she is sick, Sandra feels well most of the

time. She often goes to the TASO day

centre and sews hospital sheets. She has

been admitted twice more to hospital,

and although she gets thinner and a bit

weaker each time, her spirit remains

strong.

Rosie has been tested and is free

from HIV. When her mother dies she will

not have the additional stress of moving

elsewhere. She already has a home and

a family who care for her, with aunts

young enough to be around until she

grows up.

15

Home Visits (afternoon)

After lunch Godfrey visits a block of flats

near the centre of Kampala. Michael lives

here in two small rooms with his wife, six

children (aged from four months to 12

years), his sister and her three children.

There is no electricity and the nearest

water is a tap in the next street.

Until a year ago Michael worked in a

; factory and the family lived in a better

home. But when he started to become ill

he lost his job and he fell behind with the

rent. When they were thrown out he had

> no choice but to move in with his widowed

; sister. She is a market vendor, selling

-i cakes which she makes on a charcoal

burner in the street outside.

The children run in and take Godfrey’s

hand while he talks to Michael and his

wife, Franny. Franny feeds the baby, who

r is bouncy and chuckly, even though she

It? is HIV-positive. So is two year-old Henry.

The other four children are free of the

; virus.

Michael is worried because the shin

gles have returned on his body. The rash

itches all the time and he can't sleep at

night.

“Are you both eating well?” Godfrey

asks.

i

• home vtsft a TASO c

ckrthes or toocL

16

is not transmitted

Ugandan families have been caring for

their sick relatives for generations. There is

a great deal that family members can do to

protect the health and prolong the lives of

their loved ones with H1V/AIDS. By adopt

ing a loving, positive attitude, they can help

to maintain the person's morale. They can

also make sure that the person eats well and

gets prompt treatment for infections.

First, however, family members need to

be reassured that they are not at risk of

contracting AIDS through casual contact

with the infected person. The TASO coun

sellor demonstrates this in practical ways —

forexample by sharing cups, eating utensils

and food with the client. Relatives may also

“We try to, but with twelve mouths and

only the cake money, there isn't much to

go round."

Godfrey says he will bring more-food

on his next visit, but meanwhile Michael

should come to see Dr Katabira for some

medication for the skin rash.

Franny offers Godfrey some tea, but

he has other visits to make and leaves,

the children all laughing and shouting

goodbye.

Further down the dirt road lives Mrs

Owagi in a small earth house. A year ago

her widowed daughter died of AIDS,

leaving two children aged four and five.

Her daughter was a TASO client, so

TASO now pays the children's school

fees and also brings them soap, eggs,

milk and clothing. Mrs Owagi does not

know how old she is, but her bones ache,

especially when the rain pours down and

water rushes straight off the road into her

house. Whenever she wants drinking

water she has to buy it from a water

carrier or fetch it herself.

“I don’t know what we would have

done without TASO,” she says. “But even

so 1 worry about when I go. The children

are so young."

be worried about bedding and clothes which

become soiled with faeces or blood. The

counsellor demonstrates how to make these

items safe by soaking them in a bleach

solution or simply washing them with soap

and hot water and drying them in the sun.

Both methods kill the virus.

Material Assistance

Each TASO client receives free of charge

30 eggs a month and four kilos of milk

powder. Other foods such as cocoa-mix.

baby porridge and flavoured drink powder

are handed out as and when TASO receives

them. This is not entirely satisfactory as the

supply is erratic and the food is no:

nutritionally sound.

Second-hand clothes, whenever avail

able, are also given to families according to

need. Condoms supplied by USAID are

provided free. TASO has also produced a

leaflet in Luganda (the main local language

about the use of condoms.4

School fees are paid for some childrer

of TASO clients or deceased clients. E\en

effort is made to keep children at the same

school, unless the cost is prohibitive or the

child has to move to relatives in another

area.

Acme ivlauvcs have rejected

nedl" AIDSbccausetlieydo

|K'« the ‘hsease is spread

'' crixh'tWntiacting it thentsclves.

F- ^Asmnnnnncs the traditional system

has Wvkcn down because so

x-Jis have d.wl that the few survtvl^-^cs a.v sunplv unable Io bear the

Sxeicanug'"1 large nnmlKrsol young

.1

J

|gih

EEl S

■Ji :

^‘-^Xv tyhevs's that orphaned children

a-^ewsito. wuhm laniiliesratherthan

It no relatives are available,

kxa should lv made to place the

^F^tnendsot the deceased parents

oveixcnne prejudice against

X-^'wNvse ivuvnts luive both died of

Orphans

tSClASO helps ehents to .dentify

One of the most agonizing worries of

.Fives o. foends who cun adopt their

people with AIDS is the fate of their

after both parents have d.ed

children after they die. In Uganda it is tradi

e^xtnwlKMs also evphun to potential

tional for relatives to adopt children whose,

fo^rurems how A<‘* ts spread tn order

parents have both died. In recent vears.

Nurses discuss their feelings about AIDS during an orientation workshop.

to dispel misconceptions and overcome the

powerful stigma associated with the

disease. Together with the Save the

Children Fund. TASO also provides foster

parents with food, clothing and financial

support to enable children orphaned by

AIDS to attend school.

Training

All TASO workers - including drivers and

cleaners - attend a four-day induction

course which covers the basic facts about

HIV and AIDS, explores the emotions of

people diagnosed as being HIV-positive,

and imparts basic counselling skills (see

Appendix). Trainee counsellors start by

watching experienced counsellors at work

18

■

in the AIDS clinics for children and adults,

and later are allocated their own clients.

This course is also open to health professionals, social workers, and religious

leaders. (Twenty nuns, three Catholic

priests, one Protestant pastor and one

Islamic leader have so far completed the

course.) Visiting journalists who wish to

film or write about TASO’s work are

politely but firmly requested to participate

in this course before interviewing TASO

workers or clients.

TASO also offers a 20-week half-time

certificate course in advanced AIDS coun

selling for counsellors who already have

some training and experience.

In addition. TASO organizes orientation

AIDS workshops of one-to-three days

19

...... s of health and

xaiu'u^ IMVS

•• , community and

Catholic and

A1'""I1 |50

'■

example, have so far

Km.'''"- oikxhops.

'

Coarsening the

COUnS®,,®rJe

AIOS is very

-^«^«l''lsUaln.Allhave

<!',v l(” a,,d most

ends meet.

...... tvs to encourage their

iwmsels. the fact remains

UW I

s is

l0 (jie

^S^diose.-nseih^hoare

__ ________ ________ •

HIV-positive the strain is even greater. Yet

the pressures on them - from clients and

family members alike - are enormous and

unrelenting. Inevitably there are times

when the stress becomes too great. One sign

of excess stress is when counsellors feel that

no-one appreciates their work and there is

no point in carrying on. Stress may also

come to the surface in arguments about

management issues, or how supplies should

be distributed. When everyone is under

stress people do not notice when others are

as well. Counsellors need to feel that their

work is appreciated. They also need

opportunities to share their feelings and

frustrations.

When several counsellors were nearing

the point of ‘bum out’ TASO organised a

IB ^jl

:

Keith

TASO clion* and trainee counsellor

school teacher for 20 were killing people with this disease. We

a]Qistnct, the area in decided that they had a Christian heart,

AIDS.

so they couldn’t want to kill us. I went to

itories of people their office and how I’m training to be a

---- -------------------------------------- 1 counsellor. I was

greatly impressed

by the people there.

They were open,

■TOs ft wKhtwM

friendly and easy to

talk to. They showed

*•*’<**

me not to be afraid

that we are going to

die.

“But I am still

afraid for our people

because there is no

symptoms, so I cure. Friends may run away and abandon

fW* •fcout

disease- you. If they see anyone who might be

from time to time. sick, for whatever reason, the people in

the market say ‘Yes, that one is going.

He’ll be dead soon, you’ll see.’ If some

one has any slight fever, they say, ‘That

one may now have the insect (virus).

™JuiOirt IW

to 9° «lere'

places Who is she loving?’"

The TASO vehicle delivers food, medication and clothing to clients’ homes.

Quilt Day. Clients and workers (there is no

distinction in the way they are treated)

gathered at the TASO development unit

with pieces of cloth and began to make a

colourful patchwork quilt. Six foot long and

three feet wide, the quilt was to be sent to

‘The Names Project’, which commem

orates people who have died of AIDS all

over the United States. The TASO quilt is

the first to be made in Africa, sewn by

people with AIDS as their own memorial.

Funding

Since the establishment of TASO in

November 1987, two British organizations

- ActionAid and World in Need - have paid

TASO’s running costs (salaries, drugs, sup

plies, transport, office administration) and

capital expenditure. In 1988, for example,

the budget was S140,000, of which $40,000

was capital expenditure, mainly for the

purchase of three four-wheeled drive

vehicles. In 1989 TASO expects to spend

approximately $300,000 on running costs

and capital expenditure.

Two US organizations - Experiment in

International Living and USAID - have

contributed funds for training and equip

ment. In addition. Voluntary' Service Over

seas (UK) has provided a trainer of

counsellors for two years. The Danish Red

Cross, the German Emergency Doctor

Service, and the Pentecostal Church have

21

20

LIBRARY

DOCUMENTATION

0

t

l|lr;

f

•^‘41 I

I

■ .3

A

Bill

TASO counsellor

i-

I

Bill has been a medical assistant in Rakai

District for 28 years. He has ten children.

“Since the early 1980s we have been

seeing this disease, but at that time it had

no

name.

We

thought it was only

smugglers from

Tanzania who got it,

because they were

bewitched.

But

since we medical

people don’t believe

in witchcraft, we

were puzzled. Then

we saw people af

fected who were

certainly not smugglers, and who didn’t

move about anywhere. I tried using

strong drugs, but it still reoccurred and

people died. As time went on, there were

so many. It was such a worry, how to

cope with them all. You lose credit be

cause your patients don’t get better and

die. Some doctors won’t even treat pa

tients they suspect have AIDS. I’ve also

seen many cases wrongly diagnosed sometimes it’s just a curable disease, but

also provided assistance, and local volun

tary organizations have held fund-raising

events for TASO.

The future

Role play teaches counsellors how to listen effectively.

22

In the immediate future TASO aims to train

more counsellors to meet the rapidly grow

ing needs in Kampala and Masaka. TASO

also plans to help establish AIDS support

groups in other parts of the country. Says

Noerine Kaleeba:

“These groups must be initiated by

committed local people. We can show them

what we have done and give them training,

but it is up to each group to run itself

they stop the treatment because they

think it’s AIDS.

“Before TASO started coming to the

AIDS clinics there was no support given

to the patients after

they were told they

had AIDS. Many of

them were very

upset and they just

got up and left the

hospital. The hospi

tal staff also used

to be afraid of

people with AIDS

and either sent them

away or isolated

them. Now they are cared for just like

other patients.

“Whenever I go home, I get so many

people approaching me for advice. Many

of my people are getting wrong informa

tion, especially from the witch doctors.

When I retire in a few months time I want

to help the people at home. I lost a brother

and friends through AIDS so I really want

to do something about this great

problem.”

independently. All you need is a willing

doctor, counsellors and commitment.”

Orientation workshops will also be

organized for health professionals - from

orderlies through to senior consultants - at

all hospitals throughout the country, start

ing with Mulago Hospital in Kampala.

TASO workers are also writing a

booklet on positive living with AIDS, based

on their personal experiences. Also in prep

aration is a broadsheet explaining the aims

and work of the organization, to be dis

tributed at AIDS clinics throughout the

country.

The growing demands on TASO’s ser

vices also mean that there is a need for more

23

Conclusion

Gilbert

TASO client and counsellor

Gilbert, 36, was working as a civil servant although I sometimes have to spend a

few days in bed. I’m glad I landed in

until a year ago.

“I kept falling sick, having fevers and TASO. If I hadn't been here I would have

diarrhoea which went on and on. In thought I was the only person like this.

They understand

December 1987 I

here, so the work

learned I was HIVisn’t too taxing. I do

pr ive. My sister is

get annoyed very

a nurse and she

easily, perhaps berealised what was

cause I get tired, ft

wrong with me. At

The major thing that1®

first she didn't want

keeps me going is '

to tell me, she was

the positive feeling I

afraid of my reaction

have.”

J to the news. She

Gilbert’s wifei?

introduced me to

and

children^

Noerine, who

invited

iNutfiuie,

wiiuiiiviicu

1

--- three

---- ----> • jr

?me to visit TASO. There I met other have moved into a small house near the

In'the'same ’position. They all ; TASO office, so Gilbert can go 'home^

< looked fine and healthy, but we all had whenever he feels tired. He can also see

5the same problem.

a lot more of his children, who are. at g

“Work was getting too difficult and primary school nearby. . i

tiresome and I asked if I could become a

“As a father 1 feel much closer to my

TASO volunteer. After three months children. I have made every effort to get®'

TASO started to pay me as a counsellor, them here with me and now I want .to

As an HIV-positive person myself I can spend as much Time as possible jwitt®

talk to doctors and tell them what our - them. I must be with my family and

concerns and feelings and needs are. them while I’m here. When I'm ill, myW||

Doctors or other people without personal and children can care for me much better^

experience don't really understand, how-. than anyone else.

?

ever hard they try. It is easier too when V “Being HIV-positive isilike>b^W

counselling other people. It helps them sentenced to death. Some people-get^

when they know that I have it too.

stuck in the condemned cell and

“I have to accept that this is a disease can’t see their way out of it. But we^re^

that cannot be cured. It is fatal, but in the free to leave the cell and to live a good

meantime I can do most things normally, life until the end."

vehicles, drugs, equipment, and physical

facilities. The hired buildings currently

used by TASO in Kampala are already to

tally inadequate, and ActionAid has

pledged support for a new building which

will have three offices and counselling

rooms, a kitchen, toilets, a day centre and a

garage. This building will also be sited

within the Mulago Hospital, which pro-

24

I

TASO has provided hundreds of people

with HIV/AIDS, and their families, with

invaluable information, medical care and

material support. Perhaps even more

importantly, it has helped people with

HIV/AIDS regain their self-respect through

playing socially useful lives within their

families and communities. It has also

helped change the attitudes of many health

workers and community leaders towards

people with HIV/AIDS.

But TASO is only one small organiza

tion within a vast sea of need. Uganda needs

AIDS support groups in every town and

rural district. Many other countries in

Africa also need community organizations

of this kind.

TASO has demonstrated that a small

group of people, u ith some external assist

ance but with no previous experience, train

ing. or institutional support, can establish an

effective organization within a matter of

months. What is needed, above all, is a

combination of initiative, commitment, and

a vision of a future in which people with

HIV/AIDS will be treated with compassion

and respect rather than prejudice, ignorance

and fear.

I

1

I

i

I

vides TASO’s clients with a degree of an- ' 1

onymity and is easily accessible.

As TASO continues to expand in.

response to growing needs, it will inevit-i

ably encounter management and personnelj

problems. As in the past, the organization’!*

staff and volunteers will identify and tackle > -1

each problem with ingenuity, commitment*^

and good humour.

E

25

APPENDIX:

TRAINING

COURSES

TASO’s training courses present the basic

facts on HIV and AIDS, explore the emo

tions experienced by people diagnosed as

HIV-positive, and also impart basic coun

selling skills.

The induction course for TASO counsel

lors, for example, lasts four days - either

consecutively or once a week over four

weeks. It ’ is been found to work best with

a maximum of eight participants. The

health workers’ training workshop, with up

to 25 participants, usually lasts three days.

The courses have similar subject matter,

but their length can be adjusted to the needs

and background of the participants.

COURSE

OBJECTIVES

1. To show why the course is necessary.

2. To share experiences of HIV and to

break down barriers between people.

3. To build trust among prospective coun

sellors.

given by uninformed friends will increase

anxiety. Typical feelings:

CONTENTS

Day One

1. Share personal information: age,

education, family history.

2. Share personal experience of AIDS,

whether in oneself or in others.

6. To provide basic information about

HIV and AIDS.

7. To introduce counselling skills.

8. To emphasize the importance of con

fidentiality between counsellor and client.

26

2. Post diagnosis shock: Typical reac

tions:

“I can’t believe it.”

“I will be rejected by my family, my part

ner, my employer or society.”

“I might as well commit suicide.”

3. Share fears and anxieties about AIDS.

Day Two

1. The facts about AIDS : transmission,

stages of HIV and AIDS, prevention,

treatment of infections.

Physical signs are shaking, crying, col

lapse, numbness, inability to listen or con

centrate. The client needs time to rest and

regain self-control.

3. Denial: Typical expressions:

6. Acceptance of diagnosis: Typical

expressions:

“What shall we do now?”

“How can I live a positive life?”

“How can I help my family before I die?

7. Hope: Typical expressions:

“1 can live a positive life.”

“1 shall do everything in my power to

make my life good while I can.”

The family of the person with HIV/AIDS

may also go through the same stages of

emotional response to the disease. Family

and client will not always make the same

progress in coming to terms with AIDS.

The client may reach the positive stage

while the family is still denying that any

thing is wrong.

“The doctor has made a mistake in the

test or the diagnosis.”

“It can’t be true.”

“If I don't accept the diagnosis, it will go

away.”

“But I was unfaithful only once.”

Public reactions are more difficult to pre

dict and deal with. People may be con

siderate, sympathetic or worried. They

may isolate the person, spread gossip or

react out of fear and ignorance.

Day Four

3. The use of condoms.

4. Anger against nobody in particular or

everybody in general: God, one’s partner,

the family, society, healthy people, health

workers, oneself. Typical reactions:

Day Three

“It’s not fair.”

“It’s the fault of my partner/ the doctors/

my friends.”

2. Exploding myths. For example, some

people still believe that mosquitoes can

transmit HIV. If this were true all age

groups would be equally affected. How

ever, only sexually active people and

their babies are affected. HIV cannot

multiply inside a mosquito. It dies before

a person can be bitten by the insect.

4. To examine the objectives of TASO.

5. To examine the emotional feelings sur

rounding HIV diagnosis at a personal

level, in society and in the media.

“I don’t want to know the result.”

“What will my relatives or the public

think if I have the test?”

“What will happen to my family if I have

the test?”

ism or an appeal to the ancestors.

Explore emotional feelings associated with

HIV/AIDS. Most people go through at least

some of the following feelings (not necess

arily in this order):

1. Pre-test anxiety: clients are scared,

tense, undecided, nervous and confused

about the test. Fear arises at the prospect

of losing one’s future. Sometimes advice

Counselling skills

A good counsellor:

5. Bargaining with God. oneself, or the

family. Typical expressions:

“Please God. if I am very good will you

cure me?”

“I didn't mean to.”

1. Forms a relationship with the client

which will help the client to take control

of his/her own life.

2. Listens carefully and does not interrupt

the client.

3. Cares about the client.

4. Does not judge the client.

Sometimes the client will want to try al

ternative cures, such as witchcraft, herbal-

5. Is confidential.

27

6. Thinks about non-verbal communi

cation: takes account, for example, of the

client’s body language.

7. Relaxes, so that the client finds it easier

to relax too.

8. Thinks about sitting positions. A desk

forms a barrier between client and coun

sellor. Put two chairs close together, or sit

on a sofa or the floor next to each other.

Do not sit on the far side of the room.

9. Keeps eye contact, to establish and

maintain communication.

10. Makes a client feel comfortable.

Touching is important for warmth and

comfort, especially when people with

AIDS feel ontaminated or isolated. Hold

hands or

hand on shoulder.

11. ‘Reflects back' what the client has

said. Doing this ensures the counsellor

has heard correctly, and helps the client

think calmly about the situation. “I under

stand you said.. .“So, you are worried

you may have AIDS. Why is that?”

12. Helps the client look at new pos

sibilities by providing information and

talking about the problem.

13. Helps the client to tell his/her story.

“Can you tell me what happened/how you

feel/who you are?” Remember that every

client is unique, with different problems

and different stories.

14. Asks only relevant questions which

lead to as much information as possible.

‘Closed’ questions only receive ‘Yes’ or

‘No’ answers. Open questions yield more

information and may lead on to other

topics.

“What do you need to do?”

“What will you do first9"

“How will you do this?"

“Who might help you?”

Guidelines for responding to

clients’ questions

1. Give information, not advice. Informa

tion allows a person to make an informed

choice of their own. Advice tells people

what to do. For example, tell clients when

the AIDS clinic is held. Don’t say “You

ought to go to the AIDS clinic."

2. Ensure that the correct amount of infor

mation is given in non-frightening terms.

For example, warning a client too strong

ly about the dangers of injections or

blood transfusions could frighten the

client into never accepting either again.

Counselling role-play

* Was the client comfortable?

This exercise is useful at the end of each

workshop session. Participants can learn

from each other by watching and discus

sing one anothers' performances. Trainers

can check that participants have under

stood the lesson correctly.

* Did the counsellor touch the client in a

gentle, reassuring way?

Participants get into pairs, as ‘client’ and

‘counsellor’. The ‘client’ is given a card

with a typical question on it, e.g.

* Has the counsellor ensured that the

client has really understood the informa

tion given?

“What causes AIDS?”

“Can babies catch AIDS?”

“Should we share household articles?"

* Was the counsellor listening?

After five minutes of role-play the pairs

give a demonstration to the group.

Trainers and participants then discuss the

performance in a constructive manner,

noting the following:

3. Before giving information, find out

what the client already knows, then cor

rect any errors.

* How the client was welcomed. Did the

counsellor look relaxed and ready to help?

4. Only give accurate and relevant infor

mation.

*The sitting positions. Were they close

together?

* Was the client assured of confiden

tiality? This is especially important if the

client already knows the counsellor.

* Was the counsellor giving information

or advice?

‘ROLES’

The word ‘ROLES’ is used to help partici

pants remember the most important

points about counselling:

Relax

Open

Lean forward

Eye contact

Sitting in a helpful way

5. Be honest. It is better to say “I don’t

know” than to invent an answer. If asked

“How can I be cured of AIDS?" say “You

can’t be cured, but if you eat well, get in

fections treated quickly and reduce stress,

you can live for several years.”

6. For some questions there are no ‘right’

answers. Remember that every client is

different.

7. Look for underlying questions. Clients

often ‘present’ a simple problem behind

which a much greater one is hiding.

8. Use simple language, not medical

jargon.

15. Helps the client make a Family Plan

by responding to the following questions:

28

29

V

FURTHER READING

1. ‘AIDS Action’, an international news

letter for information exchange on AIDS

prevention and control. Distributed free to

readers in developing countries. Avail

able from AHRTAG, 1 London Bridge

Street, London SEI 9SG, U.K.

2. ‘WorldAIDS’, a news magazine repor

ting on AIDS and development.

Distributed free to readers in developing

countries. Available from The Panos

Institute, 8 Alfred Place, London WC1E

7EB,U.K.

3. ‘AIDS Newsletter’, a digest of recent

developments in AIDS research, educa

tion, clinical care, counselling, and offi

cial policies worldwide. Available from

Bureau of Hygiene and Tropical

Diseases, Keppel Street, London WC1E

7HT, UK.

4. UNICF Kampala, Our Children and

AIDS. A Guide to Child Survival, 1988.

Available from UNICEF, P.O. Box 7047,

Kampala, Uganda.

ORDER FORM

5. Gill Gordon and Tony Klouda, Talk

ing AIDS. A Guide for Community

Work, International Planned Parenthood