HEALTH INSURANCE PART-2

Item

- Title

- HEALTH INSURANCE PART-2

- extracted text

-

Developing and Costing State-Flexible

Essential Health Package (EHP) for India

C o r-'i H - 2—B.

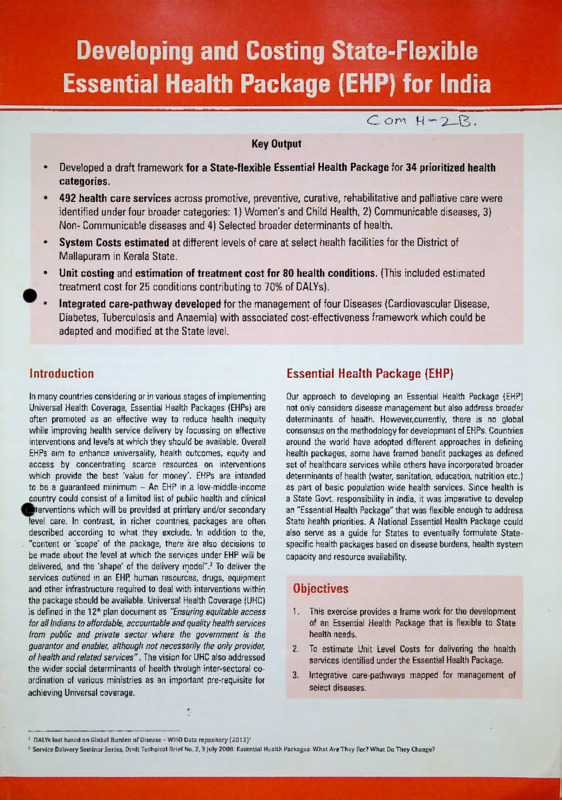

Key Output

•

Developed a draft framework for a State-flexible Essential Health Package for 34 prioritized health

categories.

•

492 health care services across promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care were

identified under four broader categories: 1) Women's and Child Health, 2) Communicable diseases, 3)

Non- Communicable diseases and 4) Selected broader determinants of health.

•

System Costs estimated at different levels of care at select health facilities for the District of

Mallapuram in Kerala State.

•

Unit costing and estimation of treatment cost for 80 health conditions. (This included estimated

treatment cost for 25 conditions contributing to 70% of DALYs).

•

Integrated care-pathway developed for the management of four Diseases (Cardiovascular Disease,

Diabetes, Tuberculosis and Anaemia) with associated cost-effectiveness framework which could be

adapted and modified at the State level.

Introduction

Essential Health Package (EHP)

In many countries considering or in various stages of implementing

Universal Health Coverage, Essential Health Packages (EHPs) are

often promoted as an effective way to reduce health inequity

while improving health service delivery by focussing on effective

interventions and levels at which they should be available. Overall

EHPs aim to enhance universality, health outcomes, equity and

access by concentrating scarce resources on interventions

which provide the best 'value for money'. EHPs are intended

to be a guaranteed minimum - An EHP in ,a low-middle-income

country could consist of a limited list of public health and clinical

Werventions which will be provided at primary and/or secondary

level care. In contrast, in richer countries packages are often

described according to what they exclude. In addition to the,

"content or 'scope' of the package, there are also decisions to

be made about the level at which the services under EHP will be

delivered, and the 'shape' of the delivery model".2 To deliver the

services outlined in an EHP, human resources, drugs, equipment

and other infrastructure required to deal with interventions within

the package should be available. Universal Health Coverage (UHC)

is defined in the 12"1 plan document as "Ensuring equitable access

for all Indians to affordable, accountable and quality health services

from public and private sector where the government is the

guarantor and enabler, although not necessarily the only provider,

of health and related services". The vision for UHC also addressed

the wider social determinants of health through inter-sectoral co

ordination of various ministries as an important pre-requisite for

Our approach to developing an Essential Health Package (EHP)

not only considers disease management but also address broader

determinants of health. However,currently, there is no global

consensus on the methodology for development of EHPs. Countries

around the world have adopted different approaches in defining

health packages, some have framed benefit packages as defined

set of healthcare services while others have incorporated broader

determinants of health (water, sanitation, education, nutrition etc.)

as part of basic population wide health services. Since health is

a State Govt, responsibility in India, it was imperative to develop

an "Essential Health Package" that was flexible enough to address

State health priorities. A National Essential Health Package could

also serve as a guide for States to eventually formulate State

specific health packages based on disease burdens, health system

achieving Universal coverage.

capacity and resource availability.

Objectives

1.

This exercise provides a frame work for the development

of an Essential Health Package that is flexible to State

health needs.

2.

To estimate Unit Level Costs for delivering the health

services identified under the Essential Health Package.

3.

Integrative care-pathways mapped for management of

select diseases.

DALYs lost based on Global Burden of Disease - WHO Data repository (2012)z

Service Delivery Seminar Series, Draft Technical Brief No. 2,3 July 2008: Essential Health Packages: What Are They For? What Do They Change?

Burden of Disease

Framework for Design of

Essential Health Package

A framework for an EHP summarized in Figure 1 was developed

based on a review of published literature and Central and State

level expert consultations with multiple stakeholders. The EHP

framework was developed around the following dimensions:

(1) needs assessment through synthesis of global experiences,

national and state level policies and programs and disease

burden; (2) priority setting through a feasibility study to identify

specific health conditions and corresponding services and (3)

establishing linkages between various components of the health

system demonstrated as care pathways proposed for select health

One of the challenges in estimating disease burden in India was

the presence of multiple data sources. These include, government

reports (reported cases), individual studies (region specific

studies), WHO data repository and other large scale surveys

like NSSO (based on nationally representative samples). Many

of these studies and health matrices differed in methodological

assessments. After a review of a range of data sources and detailed

expert consultations, a consensus was built on using the following

sources of disease burden data -NCMH projections for 2015, Global

Burden of Disease (GBD) data repository(WH0(2012), NFHS-3

(2004-2005), along with reported figures from National Census and

the Crime Bureau of India, for priority setting.

conditions (CVD, Diabetes, TB and Anaemia).

Costing Estimations at National and

Methodology

The study involved two phases of evidence collation and synthesis.

The first phase dealt with identification and development of

National Essential Health Package for India. This exercise involved

global review of evidence from 14 countries on methodologies and

approaches for developing an EHR This was complemented by

a national and sub-national level situation analysis of the Indian

health system on health services, disease burden and availability

of public health infrastructure.

34 broad health categories were identified that comprised of 492

health services in consultation with experts from Centre and States

(academia, civil society, government officials, medical, allied health

and health economics).

Regional level3

A costing exercise was undertaken for estimating unit costs

for treatment of 80 health conditions. Unit level costing was

undertaken using standard treatment protocols and expert opinion.

The costing exercise included five sets of cost components (drug^|

health workforce, diagnostics, including estimation of system

costs) for following services: Inpatient EtOutpatient Care, Operation

Theatre per hour and Delivery Room Utilization per delivery. The

estimation for the system cost was drawn from Malappuram

district in Kerala State. Our cost estimates suggests the following:

1.

India need to spend ? 1195.78 per capita to treat 25 priority

health conditions contributing to 70% of DALYs lost (As per

GBD-WHO (2012) estimates) assuming 70% of total population

access public health facility.

2.

Estimated cost for provisioning of 80 select conditions

assuming 70% of total population will access public health

facilities will be ? 1626.38 per capita.

The second phase involved:

1.

Unit cost estimation for treatment of 80 health conditions;

2.

Care pathways for population level management of selected

health conditions along with a framework for cost estimation.

Note: While preventive and promotive services are mentioned in our

framework they have not been costed in the exercise above. Two

challenges faced in this exercise were: the 1) Lack of availability of

accurate and complete data on existing preventive and promotive

services 2) Paucity of evaluation and impact assesments of

preventive and promotive services in hospitals and school health

programs

Figure 1: Framework for development of EHP

Utilizing Unit Cost Estimates for

Priority Setting

The Cardio Vascular Disease +

Diabetes Pathway

The calculated unit cost for treatment of 80 health conditions can

In this pathway Diabetes and Cardio Vascular Disease has been

combined into one in order to ensure that when population level

screening is done, given the high level of overlap between the risk

factors for both these conditions, it does not have to be repeated

be used for estimating resources required for management of

selected health condition at State as well as National level. We

have attempted development of disease management pathway for

for each disease type and that the need for confirmatory laboratory

four health conditions. Of these conditions we have populated the

tests is minimised.

pathway for Cardio Vascular Disease (CVD + Diabetes) with data

This is a complex pathway and has a number of steps.

from Census (Age Distribution), Age specific prevalence data on

CVD from NCMH projections for 2015 and unit cost for treatment

The path for management of CVD can be graphically represented as

of various Cardio Vascular Diseases along with co-morbidities as

shown below in Figure 2 and Figure 2b (with a link to the Diabetes

Management Pathway). The first part is the full pathway, while the

second includes the Diabetes Treatment Protocol which is a sub

pathway of the overall CVD + Diabetes Pathway.(For this exercise

calculated above. We have also estimated some of preventive and

promotive health services like counselling, preventive screening

(Non-Laboratory Based), and used CGHS purchase rate for

we have used treatment cost of managing Diabetes which can

be altered by State Authorities while developing State specific

laboratory based screening.

policies).

Care Pathways for select Health Conditions

In order to arrive at the cost associated with the entire Pathway,

the conditional probability data needs to be supplemented with

well-defined Care Pathway needs two inputs:

following costing data:

The precise definition of a disease or a treatment related

condition that could occur in a population.

2.

The conditional probability associated with that condition,

since it could manifest itself along any one of the pathways

that the disease or the treatment strategy could take.

With these two inputs clearly defined, the Care Pathway can be

used to answer a number of very important health systems related

questions:

1.

Cost of managing a specific disease in a population.

2.

The infrastructure requirements associated with that specific

3.

The quantum and types of human resources required to handle

The conditional probabilities taken together with the associated

costs produce a cost of ? 320.14per capita required for entire

population. It is important to note here that population level

(non-invasive) screening plays a key role. It has a high cost of

as much as Rs.65 per adult that is older than 35 years but allows

care to be focussed only on high risk individuals so that the high

cost laboratory test of Rs 199.40 can be deployed in parsimonious

manner. And, since the screening can be carried out by local

village youth, it also ends up minimising the need for scarce skilled

manpower (such as trained lab technicians).

disease.

the burden of disease in a population

Figure 2: Care pathway for Management of CVD 8 Diabetes

0.44

School Education,

— Children Below 21 Yrs

r? 8i65

Anti - Tobacco Campaign etc.

? 82.65

[

0.49

-

Low Risk

0.15

Counseling

g.55.60j 120.90

“

-j Non Compliant

0.70

0.90

§

UHC Care

I Regular Check up _

'

0.38

-T (every5Yrs|

- Medium Risk J 108.00 ? 173.30

[?J.00_7 536.42

0.31

'

- Adult >35Yrs_

? 320.14

0.30

If Hypertensive,

—“I•Treat

Treat for Hypertension

^ 0.00 667.18

0.10

|

Pathway

( ? 199.40 ]t 3.736.48

0,05

I

0.03

/ Diabetes

I

Stroke

i

? 6,077.44 7 6.848 34

-----------laboratory testing-----------

. ? 0.00. ? 0.00

,

High Risk

Treatment at Health

______ Treatment at Health

---------- facility

Facility(DH/CHCI

(DH'CHC)

0.10

Disease Score

<20

L? 0.00

? 439.90

0.80

■I Regular Monitoring

Every 3 Yrs

follow Stroke

Managment Pathway

0.80

—! No Co-Morbidity —■

Treatment at

? 0.00 7 3,767.18

Health Facfity(DK-CHC)

j? 219.007 503.30

g 4,102,76g 4.152.61 '

0.25

0.20

Opportunistic

_ Adult between

? 0.00 ? 307.81

Follow CKD

? 4,500.00 ? 5,270 90

0.90

[-{Check for Co-Morbidity [ Confirmed CVD J g 506.20 ! 4.102.76

1,318.38 7 1,383.38

0.13

High Risk

" No risk scoring

21-35Yrs

0.03

- dronic Wney Disease —|

f65.30 ? 741.31

Pathway

Diabetes

—I Follow Diabetes

? 4,469,-33 ? 5,240.23

I Care Pathway

1

Screening;__ 7

g 49.85 ? 307.81

0.95

1

-j No Monitoring

Low Risk

| ? 55.60 i ? 105.45

ItQJXL 7 284.30

DAL Assumptions:

Costing exercise were based on facility based treatment cost and doesn't include costs incurred on outreach activities, district and state level admin cost, preventive,

promotive, rehabilitative and palliative services.

Administrative overheads were taken at 10% of treatment cost estimation.

Figure 2b: Sub- Pathway for Management of Diabetes

The School based education campaign for children below the age

of 21 accounts for almost a third of the total cost of ? 320.14. This

expenditure would need to be examined very carefully as there are

resource limitations. Laboratory based opportunistic screening for

individuals aged more than 35 and comprehensive diet counselling

adds almost Rs.255 to the overall expenditure. These approaches

may need to be re-examined if there are budgetary constraints.

Health education campaigns and opportunistic screening for

Key Policy Recommendations

1.

Service packages are critical as it serves as a

blueprint to assess the kinds of resources needed to

strengthen the health system for the delivery of the

services.

2.

Based on the care pathway the burden of Cardio

Vascular Diseases can be managed by Indian States

at Rs. 320.14 per capita using the proposed UHC

Care pathway as against Rs. 349.83/- per capita

estimated using the current conventional treatment

based pathway.4

3.

A national level costing exercise with more

representative sample is needed for developing

efficient resource allocation in Health Sector.

younger adults are dependent on State level capacity and initiative.

4 Costing on Conventional pathway is based on following assumptions

RiskofCVD is negligible in < 20 Yrs. (2) Prevalence ofCVD is 9.86% in person >20 Yrs; (3) 20 % of total population does regular preventive check-up of which 90% of high risk

population follow regular treatment protocol. (4) cost of managing emergency is Rs. 6077 which is treatment cost of managing hypertensive stroke.

.C'lON

PUBLIC

HEALTH

FOUNDATION

OF INDIA

NORWEGIAN EMBASSY

This study was conducted with the generous support of the

Royal Norwegian Embassy (RNE)

Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI)

Institute for Studies in Industrial Development (ISID) Campus

4,

Institutional Area, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-1 10070

Phone No.: 011-49566000, Fax No.: 011-49566063 www.phfi.org

For queries please contact:

Pallav Bhatt, Varada Madge (pallav.bhatt@phfi.org, Varada.madge@phfi.org)

Research Team: Mr. Pallav Bhatt, Ms. Varada Madge, Dr. Nachiket Mor, Dr. Avtar Singh

Mr. Navneet Jain, Dr. Priya Balasubramaniam

Oer>3 W"

Tropical Medicine and International Health

VOLUME 2. NO 7 PP 654,-671 JULY I997

A health insurance scheme for hospital care in Bwamanda

district, Zaire: lessons and questions after 10 years of

functioning

Bart Criel and Guy Kegels

Public Health Department, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium

Summary

A voluntary insurance scheme for hospital care was launched in 1986 in the Bwamanda district in

North West Zaire. The paper briefly reviews the rationale, design and implementation of the

scheme and discusses its results and performance over time. The scheme succeeded in generating

stable revenue for the hospital in a context where government intervention was virtually absent

and external subsidies were most uncertain. Hospital data indicate that hospital services were used

by a significantly higher proportion of insured patients than uninsured people. The features of the

environment in which the insurance scheme thrived are discussed and the conditions that

facilitated its development reviewed. These conditions comprise organizational-managerial,

economic-financial, social and political factors. The Bwamanda case study illustrates the feasibility

of health insurance - at least for hospital-based inpatient care - at rural district level in sub-

Saharan Africa, but also exemplifies the managerial and social complexity of such financing

mechanisms.

keywords voluntary health insurance, moral hazard, hospital care, district health systems,

research, rural Zaire

correspondence Bart Criel, Public Health Department, Institute of Tropical Medicine,

Nationalestraat 155, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium

Introduction

stable revenue to fund the cost of health care provision,

its capacity to reduce financial barriers to health care

Health insurance as a source of finance for health care is

utilization and its redistributive effects (Mills 1983).

a system in which potential consumers of health care

There is great interest in, and sometimes indeed strong

make an advance payment to an insurance scheme,

advocacy of the introduction or expansion of

which in the event of future health service utilization

insurance-based health care financing schemes in

will pay the provider of care some or all of the direct

Africa (Abel-Smith 1986; Arhin 1995a; Vogel i99oa;b;

expenses incurred (World Health Organization 1993a).

World Bank 1987,1993). Several international

The existence of risk is the fundamental rationale for

organizations consider the study of insurance systems

in developing countries as the priority area in the field

insurance. The reasons for encouraging health

insurance are its potential for raising additional and

of health care financing (UNICEF 1992; WHOi993b;

EU 1995). This plea for the development of health

This is the revised version of a paper presented by Bart Criel at

the international colloquium ‘The African Hospital’ held at the

Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp (6-8

December 1995).

654

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

insurance in developing countries is in line with the

shift towards private sources of finance for health care,

the most notable change during the 1980s being the

introduction and increase in user fees for government

VOLUME Z NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

services (Creese 1990; Van Lerberghe 1994). In this

respect health insurance is a policy option which fits in

with the current international trend towards the

limitation of state activity and privatization (Criel et al.

1996).

presented. Barr Criel worked in the Bwamanda district

from September 1986 to July 1990. initially as a general

medical officer and later as district medical officer. The

Bwamanda insurance scheme is still functioning to date.

In our view, this case study illustrates the feasibility of

The introduction of national compulsory health

health insurance at rural district level in sub-Saharan

insurance schemes is being considered in some sub-

Africa, but also exemplifies its managerial complexity

Saharan African countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and

and difficulties encountered in its evaluation. The paper

Zimbabwe (WHO 1993a). This is unlikely to be an

hopes to contribute to clarifying the many issues and

equitable and efficient financing option in a context

questions district health planners face when considering

where only a minority of the population would be

health insurance in similar environments.

covered, for instance only formal sector employees

(Korte et al. 1992), and where the administrative

capacity required for the adequate management of such

schemes is limited. Vogel in his overview of formal

health insurance systems, both publicly and privately

Some theoretical considerations relative to

health insurance

What is health insurance about?

organized, in 23 sub-Saharan countries concludes that

the development of health insurance has neither

Insurance rests upon the principle of risk-sharing

promoted greater equity in access to health services by

between many people. It reduces individual uncertainty

the poor nor has it permitted greater access (Gruat 1990;

concerning the timing and amount of future possible

Vogel 1990b). The small middle class seems to have

expenses that may be incurred and thus contributes to

benefited most.

an increase in well-being (Dubuisson 1995). Insurance

Locally developed and district-based insurance

relies on the fact that what is unpredictable for an

schemes targeting poor rural self-employed populations

individual is highly predictable for a large number of

remain relatively rare in developing countries. These

individuals. The principle is one of insurance based on

‘community-based’ health insurance schemes are less

risks or probabilities and not one of prefinancing or

common than formal social security systems despite

prepayment for known future events (Mills 1983).

their a priori attractiveness (Baza et al. 1993; Carrin

Premiums ate paid to an institution which compensates

1987; Dumoulin & Kaddar 1993). Only within the last

— partly or totally - any insured victim of the event for

10 or 15 years have experiments in rural health

the financial loss resulting from the event. In the case of

insurance catering for self-employed people been

health insurance this insurance institution may also be

developed in sub-Saharan Africa (Shepard et al. 1990;

the health care provider. Such a situation is referred to

Chabot et al. 1991). There is still little analytical

as direct insurance (Kutzin & Barnum 1992), or a direct

information available about such health insurance

pattern of insurance (Roemer 1969).

schemes (Arhin 1995b), and further operational research

on the design and organization of insurance schemes

covering people in the informal sector is urgently needed

(WHO 1993a; Noterman et al. 1995).

We discuss one of the few well-established

655

Adverse selection and moral hazard: a brief overview

In voluntary health insurance schemes it is important to

minimize the preferential selection of high-risk

experiments in health insurance at district level in sub-

individuals, a phenomenon the insurance industry calls

Saharan Africa: the insurance scheme for hospital care

adverse selection. Adverse selection occurs when those

in the Bwamanda district in Zaire. Its origin, design and

who anticipate needing health care choose to buy

implementation have been documented (Moens 1990;

insurance more often than others: for instance, in the

Moens &C Carrin 1992; Ilunga 1992). Our principal aim

case of health insurance, patients with chronic diseases

is to focus on the evaluation of this scheme, on the

or individuals with a high predictability of health service

conditions for reproducibility, and on avenues for future

utilization (pregnant women for instance). It occurs

research. Institutional features and the practical

when insurance suppliers lack full information about the

organizational details of the scheme will first be briefly

risk of individual insured persons or when, on grounds

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Cnel and G. Kegels

VOLUME 1 NO 7 PP 654-671 JULY 1997

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

of equity, they offer insurance policies based on

security systems in industrialized countries is facing. It

community-rated premiums (Arhin 1995b). Community

has contributed to an increase in unjustified

rating refers to a policy in which the premiums are

consumption of health services at inappropriate levels of

related to the risk of the group in its totality; that is, all

care in the health pyramid, and the achievement of an

subscribers will pay similar premiums (except for

adjustments for family size). The premiums will thus not

integrated health system, i.e. a system where the various

tiers have a specific role and function in a

vary according to age, sex, health risk, occupation, etc.,

complementary way (Unger & Oriel 1995), may be

as is the case with actuarially based premiums.

jeopardized. The consequences are cost inflation, loss of

Community rating discourages those of low risk from

individual and collective autonomy, excessive

purchasing insurance while making it more attractive to

medicalization, etc. (WHO 1977). Hence one of the

high-risk individuals. The occurrence of adverse

major challenges a district health planner in a

selection is a function of the nature of the subscription

developing country will face when implementing health

unit (individual or household) and also of the

insurance is the need to minimize the undesirable and

proportion of people who join the scheme. The former

potentially harmful effects of enhanced financial

determinant can be controlled in the design of the

accessibility to health services.

scheme; the latter cannot, unless a minimum level of

participation is imposed before the insurance scheme

can function.

Moral hazard also has received considerable attention

from the insurance industry. It is defined by Mills (1983)

as ‘the tendency of individuals, once insured, to behave

in such a way as to increase the likelihood or size of rhe

Bwamanda district

Bwamanda district is located in the north-west of Zaire.

risk against which they have insured’. Moral hazard

It covers an area of 3000 km1 and had a population of

thus results in an ‘over-consumption’ of health services

about 158 000 in 1994. About 90% of the population are

for health problems that could find an adequate solution

farmers. Their annual per capita income is about USS

at lower levels of the system. Moral hazard can be

75. The health services in this district are based on a

induced by the patient himself, but also by the health

two-tier system: a network of 13 health centres scattered

care provider’s behaviour (Donaldson & Gerard 1993).

throughout the district and a 138-bed referral hospital.

It is likely to occur in a context where the organization

The diocese is the formal owner of the hospital but in

of the health services system lacks basic rationalization:

functional terms the Bwamanda hospital fully acts as a

for instance, a situation where people insured for

referral hospital for the Bwamanda area in accordance

hospital care have unlimited access to hospital services

with prevailing national health policies.

in the absence of an effective referral system between the

The development of the health services in Bwamanda

different levels of care. The well-documented case of the

was one of the activities of a larger integrated

health insurance experiment in the Masisi district in

development project, the CDI Bwamanda (Centre de

eastern Zaire is illustrative in that respect (Noterman et

Developpement Integral). The CDI Bwamanda is a

al. 1995). Preliminary data on the Nkoranza scheme in

Zairean non-profit organization; it was established at

Ghana also indicate the occurrence of moral hazard

the end of the sixties and gradually developed a wide

(Moens 1995). Methods have been developed in order to

range of activities in other fields than health care, such

counteract moral hazard. One of the most widely used

as agriculture, communications infrastructure, primary

methods, but not necessarily the most effective one, is to

education and rural development. It received

considerable external support in terms both of finance

institute co-payments or co-insurances. The insured

persons then pay part of the fee at the time of health

and of human resources. Government subsidies always

service utilization. Co-payment may be useful, not only

remained very limited.

in limiting excess demand, but also in generating

additional resources.

The occurrence of moral hazard is considered one of

the major problems that health insurance under social

656

Rationale, design and implementation of the

Bwamanda hospital insurance scheme

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

By the mid-eighties the district health system had

reached a relatively high level of functioning. Quality

health care was accessible to the vast majority of the

population through the establishment of an integrated

VOLUME 1 NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

of these health institutions. These salaries always

district health system. Most of the population had

remained very’ poor.

In the case of a hospital admission a flat fee per type

reasonable access to a health centre (95% lived within

7 km of a health centre). The population covered by a

of admission was paid, with 5 possible fees according to

health centre ranged between 3000 and 13 000

inhabitants. The villages in the area of responsibility of

the type of care required. In practice this amounts to a

simplified diagnosis-related groups system: one fee for

each health centre were organized in rural committees

for integrated development (Comites Ruraux de

admission in paediatrics, internal medicine or

Developpement Integral or CRDI), which met monthly

gynaecology, and 4 progressively higher fees for surgical

to discuss health issues as well as other problems related

interventions categorized from minor to major (Table

to development. In 1986, the average utilization rate for

1). In 1985 revenue from patients in the Bwamanda

the curative clinics at health centre level was 0.6 new

hospital constituted 40% of the total hospital revenue

cases/inhabitant/year; coverage for antenatal care was

(Ilunga 1991). The remaining 60% came from subsidies

84%; coverage for measles vaccination was 50%. The

from the mother organization, i.e. the CDI Bwamanda,

annual hospital admission rate was about 30/1000.

from external funds of the Belgian bilateral aid agency

Referral and counter-referral systems functioned

and from various NGOs.

The fee schedule presented in Table x clearly

reasonably well.

indicates that the functioning of the Bwamanda

In the mid-eighties many of the health centres in the

district succeeded in recovering their recurrent costs

hospital was largely subsidized. For instance, rhe total

through community financing mechanisms. These costs

fee charged for a Caesarean section in 1985 (category

related to staff salaries (on average three staff members

surgery IV) was USS 5, which is obviously inadequate to

in each centre: a nurse, a nursing aid and a general

cover actual costs. Surveys of hospital recurrent cost

hand), drugs, medical and other minor supplies. They

analysis carried out in relatively similar settings support

did not include depreciation costs, nor the cost of the

this statement. A recurrent cost analysis of an

monthly supervision visits. The method of payment was

effectively functioning rural district hospital in Uganda

a flat fee per episode of illness and episode of risk. In

showed that the average cost of a single major surgical

1987 for instance, 9 of the 2.1 health centres in the

operation was USS 11 in 1992. If the cost of 10 inpatient

district managed to recover these recurrent costs; the 12

days (an average length of stay in hospital for a patient

other centres reached levels of cost recovery ranging

receiving major surgery) is added to this figure, then the

between 73% and 98% (Bwamanda Health District

total cost was USS 30 (unpublished data). A study of

1987). Such high levels of cost recovery were certainly

unit costs for in-parient services carried out in 3

not exceptional in Zaire and are confirmed by the results

Zimbabwean hospitals identified an average cost for

of a large study by USAID on the financing of 10

major surgery of approximately USS 35 (UNICEF

effectively functioning health districts in Zaire

1996); another study in 6 Malawi hospitals identified a

(Resources for Chile! Health Project 1986). Other data

pertaining to Zaire have indicated an average cost

cost per single inpatient (all services together) ranging

from USS 20 ro S 30 (Mills et al. 1993); and a Medicus

recovery rate for health centres of almost 50% (Pangu

Mundi International (MM1) survey of 59 non

1988). The USAID study also indicated that the salaries

of hospital and health centre staff constituted,

governmental hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa identified

a median cost per inpatient of USS 33 (Van Lerberghe

respectively, 50% and 35% of the recurrent expenditure

et al. 1992).

Children

Adults

657

Paediatrics

intern, med

gynaec.

Surgery I

Surgery II

Surgery III

Surgery IV

30 Z

120 Z

too Z

TOO Z

150 Z

150 Z

200 Z

200 Z

250 Z

250 z

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

Table 1 1985 fee structure before the

introduction of the health insurance

system (in 1985, 50 zaires = 1 US $).

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

VOLUME Z NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY I997

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

A health insurance scheme for hospital care

•

one annual subscription period at a time coinciding

with the purchase of the coffee and soy bean crops

Problem definition

(months of March and April);

In the eighties the Bwamanda hospital faced a steadily

increasing cost of medical care due to inflation, and

•

the same time increasing reluctance of external donors

the family as subscription unit, with individual

premiums;

hospital charges had to be raised several times a year. At

•

risk coverage limited to hospital care, with a 20%

•

decentralized collection of premiums at health

to subsidize the hospital’s recurrent costs and virtual

co-payment rate;

non-existence of government funding led the health

district managers to identify other stable sources of

centre level;

funds. In addition there was a problem of financial

accessibility to hospital care, ar least during certain

•

periods of the year, and payment of hospital fees

implementation in the whole district at the same

time, and only for the district population;

became an increasing problem for rhe poor rural

population of Bwamanda district because of fluctuating

availability of cash income due to seasonality of crops.

Some patients referred from rhe health centre only

arrived at rhe hospital after several days due to the time

needed to find the necessary funds. Hence the challenge

for the district management team was to design a

financing strategy with improved access to hospital care

for all people in need while maintaining the hospital’s

financial viability.

Design and organization of a hospital insurance plan

The district management team discussed and compared

various possible financing alternatives. The following

criteria were used: political and social acceptability,

ability to pay, risk-sharing potential, likely effect on the

financial viability of the hospital and likely effect on rhe

hospital’s financial accessibility. An insurance scheme

was considered superior to the current system of fees per

type of hospital service. The team identified the main

variables relevant to a health insurance scheme about

which a decision needed to be taken: What nature of

insurance premium payments? What rime and frequency

of payments? Which unit of membership? Which

services covered by the insurance scheme? Should co

payments or deductibles be considered?, etc. The

discussion was pursued with the nurses heading the

health centres during one of the regular workshops

organized for them in Bwamanda. The various options

concerning the above-mentioned variables were

analysed and compared. Eventually a consensus was

reached on the following features of rhe scheme:

•

658

a cash payment of a premium identical for all,

•

management by the district management ream.

Finally, the basic elements of the concept of insurance

were presented to community representatives of each

health centre. They expressed a preference for a scheme

without co-payments, but the district management team

thought it wise to have a 20% co-payment, which

constituted a financial security margin in a context of

high inflation and could act as a deterrent to

unnecessary hospital utilization. At rhe specific request

of the nurse in charge of the maternity department, an

exception was made and no co-payment was charged for

insured patients using maternity services. The rationale

of this request was the concern to increase the workload

at the maternity unit for the training of the local

midwifery students. Women who had not attended

antenatal care during their pregnancy, however, were

not covered by the insurance and had to pay the full fee.

Questions were also raised concerning the possible

situation of families who joined the scheme but did not

undergo any hospitalization. Would they then get a

refund? This concern is not surprising. Indeed, the

widespread local mutual help mechanisms, such as

traditional solidarity mechanisms within the extended

family and mutual aid associations (tontines in

francophone Africa, or ROSCAs, Rotating Savings and

Credit Associations, in the anglophone literature) are

very often based on a principle of voluntary balanced

reciprocity (Dubuisson 1995) rather than on a principle

of solidarity. Eventually, however, the majority of the

community representatives agreed with the launching of

this innovative financing scheme in 1986.

The first subscription period was the month of March

independent of age, sex, domicile, health status,

1986. During this one-time annual enrolment period of

etc., i.e. a community rating system;

one month, membership premiums were collected by the

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

VOLUME 2 NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY T997

Tropica] Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

staff of each health centre and representatives of the

village committees. The level of the premium was

empirically set at 20 Zaires, which approximately

corresponded to USS 0.3. This amount was deemed

Referral from health centre to hospital was mandatory if

the insurance was to take effect. Table z presents an

overview of the hospital fee structure for the month of

September 1986.

affordable: it was less than half the flat fee charged for

an outpatient consultation at health centre level. Twenty

Results

Zaires was also the equivalent of the price paid to

Bwamanda farmers for 2 kg of soy beans, a common

Financial impact

crop in the area. As proof of payment of the premium, a

The interest shown by the Bwamanda community in this

stamp was affixed to the family record kept for each

voluntary insurance scheme for hospital care was

family at the health centre. A census of the district

overwhelming and beyond most expectations. In 1986,

population had been carried out in 1985 and 1986, and

32600 people - i.e. 28% of the district population -

on that occasion a family file had been opened for each

joined the scheme within 4 weeks. The financial balance

household. In addition a membership register was

opened at each health centre. The nurses in charge of the

health centres eventually handed in the collected monies

to the district health services administrator, who

deposited the funds in a separate health plan account.

The health insurance scheme was not run by a separate

‘third party’ institution; it was managed by the district

health authorities themselves and can thus be described

as a direct pattern of insurance. On the whole, the

administrative costs incurred for the practical

organization and management of the insurance scheme

remained relatively low. These costs covered transport

and stationery expenses, staff bonus payments, and

salaries of the scheme’s administrating and clerical staff.

Data for rhe period 1987-89 indicated total

administrative costs ranging between USS 510 and 1800,

i.e. between 4 and 6% of total expenses (Shepard et al.

1990). Recent data for the 5-year period 1990-95 reveal

that the yearly cost of administering the scheme ranged

after the first year of operation was positive, with a

small surplus of approximately USS 1300. In the

following years the membership rates steadily increased,

indicating a high degree of social acceptability

(Figure 2). In 1987, 60000 people joined the scheme, and

in 1988, 80000. The membership rate tended to stabilize

around 60-65%. Each year the subscription charge was

adjusted in line with inflation. The value of the charge

remained approximately equivalent to the purchasing

price of 2 kg of soy beans - approximately one-third of a

US dollar-though with small variations over the years.

It is striking that this interest remained even during

the dramatic social and political turmoil which Zaire

has been experiencing since the beginning of the

nineties. This is somewhat surprising, since one would

expect expenditure for a hospital insurance scheme to

drop on people’s priority list when the daily search for

food becomes a major challenge. However, membership

between c. USS 1000 and $ 3500, i.e. between 5% and

10% of the total expenses (These costs have been

Table 2 Hospital fees in September 1986 (in Zaires) (in 1986,

calculated through a conversion of Zaires into USS at

the average annual exchange rate was 61 Zaires for 1 USS)

the exchange rates prevailing ar that time. The sky

rocketing inflation rates, especially in the 1990s, make

cost estimates in foreign currency a perilous exercise.

This may contribute to the explanation for the variation

in administration costs identified in the period 1990*995)The routine functioning of the insurance plan can be

summarized in a decision tree in which administrative

and managerial procedures are presented in a sequential

way (Figure 1). It is important to stress that members of

Type of admission

Paediatrics

Internal medicine

Gynaecology

Maternity

Surgery I

Surgery II

Surgery III

Surgery IV

Fee for uninsured

patients

Fee for insured

patients

S1j

500

Soo

^qq

3JO

Joo

?00

9OO

the scheme who used the hospital outpatient department

without being referred by their health centre could not

benefit from the insurance, except in emergencies.

659

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

the use of the maternity services was free of charge for insured

pattents only tf they had attended antenatal care.

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

VOLUME! NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

Level In the District

Health Services System

Managerial and

accounting procedures

Patient at the health

centre's out-patient

department: consultation

by nurse

In case of referral to the

hospital, check for

subscription proof on

family file (stamp +

subscription number):

If not member:

‘ordinary1 referral

If member

the subscription

number is notified

on the referral

ticket

In case of doctor's

decision to admit the

patient:

Arrival at hospital’s

out-patient department:

consultation by medical

doctor

If member:

cross-check for

subscription

number in

hospital-based

register'

Hospital's accounting

department

If cross-check

positive: admit

patient at reduced

fee (20% of

regular fee) and

transfer of 80% of

regular fee from

health insurance

fund to the

hospital accounts

If not member

payment of

regular hospital

fee (100%)

If cross-check

negative: further

investigate the

patient's

subscription

status

'Each individual health centre team notifies names and subscription numbers of all people who joined the scheme in a register which

is transferred to the hospitals's accounting department at the end of the enrolment period.

Figure I

Managerial flow-chan for referred and admitted patients (adapted from Moens Sc Carrin 1992).

dropped significantly from 66% in 1991 to about 40% in

membership rates, together with the option to have the

severe ethnic tensions in the Bwamanda area, with a

household as subscription unit, greatly reduced the risk

climate of social unrest, were probably responsible for

of a preferential selection of high-risk cases (i.e. adverse

the fall in subscriptions. In 1994 the enrolment period

selection). These membership rates are in fact a slight

was preceded by the nationwide change in currency

underestimate of the real subscription rates, since a sub

from anciens to nouveaux Zaires, limiting cash

population of a few thousand people in the Bwamanda

availability for many people.

health district - most of them employees of the different

The size of the population joining the scheme made

660

genuine risk-sharing arrangements possible. High

X992, and from 66% in 1933 to 41% in 1994. In 1992

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

CDI project services - are covered by mandatory

VOLUME Z NO 7 PP 654-672- JULY 1997

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Figure 2

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

Membership rates for the period 1986-1995

employer-organized health insurance schemes which

revenue for the period 1985-89 are presented in Table 3.

provide them and their families with free health care.

Revenue raised from payments for hospital care

They did not have an immediate incentive to join the

(‘internal’ or locally generated revenue) doubled from

scheme. If some of them paid the insurance premium out

USS 21180 in 1985, the year before the start of the

of their own pocket, it was with the objective of being

insurance plan, to USS 44 475 in 1989. Internal revenue

insured if they lost their job and thus the benefit of free

is made up of direct payments by non-insured patients,

care.

The evolution and the sources of Bwamanda hospital

prepayment of employer-organized health care schemes,

reimbursements to the hospital by the insurance fund

Evolution of hospital revenue (1986-1989) in USS. (Average annual exchange rates: 1 SUS for 50 Zaires in 1985, 61 Zaires in

1986,128 Zaires in 1987,187 Zaires in 1988, 400 Zaires in 1989)

Table 3

Source of hospital revenue

A. Internal revenue

A.1. Refunding by insurance fund for insured: i.e. 80% of

regular hospital fees

A.z. Co-payment by insured: i.e. 20% of regular hospital fees

A.3. Prepayment by employers for health care of employees

and their families

A.4. Direct revenue from patients*

Total internal revenue (% of total hospital revenue)

B.

Subsidies’* and gifts (% of total hospital revenue)

Total hospital revenue (A + B)

2985

1986

1987

1988

1989

—

—

10,670

2,670

8,620

14,700

M5S

3.675

19,630

4.900

—

zi,i8o

«,4«5

“.<55

10,990

10,870

9.635

7,010

13,810

21,180

(41%)

31.460

(61%)

3^35

(8z%)

35,010

(75%)

44.475

(79%)

30.635

(59%)

20,040

(39%)

7,200

(18%)

11,515

(15%)

11,910

(11%)

51,815

(100%)

51,500

(100%)

39.835

(lOO°/o)

46,535

(100%)

56,385

(100%)

Source of data: Ilunga (1992) Sc Bwamanda Health District (1985-1989).

•Non-insured self-employed patients.

•*The last government subsidies for the Bwamanda hospital were in 1984. Since then the only external hospital funding came

through the CDI project.

661

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

6,135

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

and co-payments by insured patients themselves.

51 815 in 1985 to USS 56 385 in 1989. Table 3 shows

Between 1986 and 1989 there was a clear trend for the

clearly that the relative proportion of internal revenue in

revenue from the insurance scheme (reimbursements and

total hospital income increased dramatically from 41%

co-payments) to increase. The insurance ensures the

hospital a source of income which is stable because the

in 1985 to 79% in 1989.

number of non-paying patients is much reduced.

Direct payments by non-insured persons decreased by

almost half from US$ 11 655 in 1986 (when 72% of the

district population was not insured) to USS 6 135 in 1989

662

VOLUME 2 NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Hospital utilization data

In 1986 hospital admission rates for the insured and non

insured population were 36.2 and 24.8 per thousand,

(when only 39% of the population was not insured). An

respectively. In 1988 these rates were 35.6 and 24.6 per

a posteriori analysis of the evolution in hospital fees

thousand, respectively (see Table 4). These differences

indicated that the fee levels for non-insured persons -

are statistically highly significant. Hospital data for the

and at the same time the 20% co-payments for the

year 1989, based on a one-in-io sample from the hospital

insured - had in fact dramatically increased over the

register, showed that insured patients had specific

same period. A Caesarean section, for instance, was

hospital service admission rates 1.9-6.7 times higher than

charged at approximately USS 5 in 1985, USS 15 in 1986,

non-insured patients not covered by employer-organized

USS 14 in 1987, USS 19 in 1988 and USS 28 in 1989 (see

schemes (Shepard et al. 1990). More recent data for the

Figure 3). On the other hand, subsidies (external

12-month period April 1993 - March 1994 revealed

revenue) to the hospital decreased in 1989 to about one-

admission rates of 49 per thousand for the insured and

third of the 1985 level (from USS 30 635 to n 910),

24.9 per thousand for the uninsured. The latter figure can

whereas total hospital revenue increased from USS

be further split into 17 per thousand for uninsured self-

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

VOLUME Z NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

Hospital admission rates in insured and non-insured

populations of the Bwamanda district (years 1986 and 1988).

Table 4

district frequently claimed to live within the district

boundaries to be eligible for subscription to the

insurance plan during the enrolment period. They had

Year

Admissions/

insured population

(in per thousand)*

Admissions/

non-insured‘*

population

(in per thousand)*

1,181/32,614

(36.2 7-)

2,863/80,495

(35.6 -n

1.133/85,998

(14-8’/“I

1,100/48,749

(i4.«-n

their names added on the family file of a ‘host’ family

(which was often composed of relatives). This happened

X‘ and

P-value

mainly in the areas of the two Bwamanda town health

centres and in the areas of two health centres situated at

the edges of the district. Hence the figure of 49 per

1986

1988

(x‘ = IT35

p < 0.001)

thousand admission rate for insured persons from the

(X‘ = 11 %

district is probably a slight overestimate.

Table 5 also shows that in the period I993“94 about

p < 0.001)

15% of all admissions (1078 out of 7362) were patients

‘These ratios are considered to be true proportions, which in

reality they are not since the numerator may contain several

admissions for one same individual.

•‘The data concerning the non-insured population also include

admissions of patients covered by employer-organized schemes.

living in neighbouring districts. This is not a new

finding: Bwamanda hospital has always been a facility

with a substantial proportion of users from other

districts. Data for the year 1987 indicate that 17% of

admissions (691 out of 4090) were patients from outside

employed persons and an estimated 184 per thousand for

the district (Bwamanda Health District 1987). In 1995

people covered by an employer-organized scheme (Table

this figure increased to 20.4% (1599 out of 7843)

5). During the last 3 or 4 years people from outside the

(Bwamanda Health District 1995).

Table 5

Hospital admission data for the period 1/4/93-31/3/94

Number of admissions according to patient origin

Hospital service

Paediatrics

Gynaecology

Internal medicine

(male + female)

Surgery men

Surgery women

Maternity

Intensive care

Total admissions

Denominator

Admission rate

Insured from

district

Non-insured

from district

Employer

organized

schemes in

district

Out of district

Total

1,267

178

547

168

39

201

221

21

41

131

68

356

1,788

406

1,146

452

370

1,119

939

4.972-

20

15

82

326

851

17

32*9

99

461

78

87

35

32Z

1,078

567

504

1 >2-65

1,686

7.362-

IOI.353

49 per

thousand

50,131

17 per

thousand

2,500*

184 per

thousand

non-applicable

non-applicable

non-applicable

non-applicable

24.9 per thousand

‘This figure is an estimate.

Notes:

- Patients from the trypanosomiasis ward are not included in this table.

- Most of the patients admitted in the intensive care ward are transferred to other wards afn-r -> f-... j

counted twice and the real number of admissions is therefore lower.

W

663

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

L

,

.

.

theSC admlssl0ns ar' thus

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

VOLUME 2 NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

This partem of higher hospital admission rates for the

systems exist. The group proposed a framework for the

insured population may, generally speaking, be due to a

evaluation of financing schemes based on the following

combination of moral hazard and better access for those

criteria (WHO 1993a): the level and reliability of

who need it. Within rhe limits of the available

resources raised; the efficiency and the equity of the

information it is difficult to assess the relative

scheme; its viability in terms of social acceptability; and

importance of each single possible cause. The fact that

finally its health impact. The group recognized that

insured patients can benefit from the insurance scheme

currently information is least available for the last area

only when referred by a health centre and the system of

of evaluation of health gains.

The social acceptability of the Bwamanda scheme

co-payment at hospital level are factors which a priori

tend to counteract any substantial degree of

seems beyond dispute given rhe high subscription rates.

inappropriate hospital utilization.

The other evaluation questions relating to the scheme’s

It is important to acknowledge the fact that the

financial performance, to its effectiveness, efficiency and

equity are discussed in more detail in this section. The

increment in hospital utilization by the insured

population seems to be highly variable. The data in

initial objectives set forth by rhe district managers were

Table 6 indicate that excess use is particularly high for

as follows: on the one hand there was rhe need for a

surgical services, both female and male, but that it is

stable source of local revenue allowing the hospital to

hardly apparent for internal medicine services. The very

function properly virtually without government funding

high admission rates for rhe (small) population covered

and with most uncertain future levels of external

by employer-organized prepaid health care schemes are

subsidies. On the other hand, there was the concern to

not surprising, for these patients - rhe majority of whom

keep hospital fees at an affordable level for rhe

live in and around Bwamanda township — have no

population of rhe district so that financial accessibility

financial cost to bear in case of hospital admission.

was maintained.

Discussion: What lessons can we learn from

the Bwamanda experience?

resources?

Can we regard the Bwamanda insurance scheme as a

success?

Financial performance: attraction of additional

The Bwamanda scheme evidently succeeded in

generating reliable and stable resources for the

functioning of the hospital. Locally raised revenue

A recent WHO study group acknowledged the fact that

virtually doubled between 1985 and 1989, even though

many different criteria for rhe evaluation of financing

total revenue remained more or less the same around

Table 6

Hospital admission rates for the period

Admission rates in

per thousand

Insured

population

Uninsured

population

Paediatrics*

Gynaecology*

Internal medicine*

Surgery men*

Surgery women*

Maternity*

Maternity**

12.5 per thousand

3.3 per thousand

0.8

'-7

5-4

4-4

J«

II

27.6 per hundred

expected deliveries

4

o-4

0.3

1.6

4.1 per hundred

expected deliveries

Population

covered by

employer-organized

pre-paid schemes

Ratio admission

rate insured/

admission rate non

insured

88.4 per thousand

3.8

3-4

i-35

11

8-4

16.8

6.8

12.8

11.6

29 per hundred

expected deliveries

*The denominator is the general population.

••The denominator is the number of expected deliveries (birth rate is 40 per thousand).

664

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

12

4-9

VOLUME Z NO 7 PP 654-672. JULY 1997

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

approximately US$50 000 a year. The precise amount of

subsidies allocated to the hospital was in fact never

decided on a predetermined basis — at the start of every

new budgetary year for instance. The hospital thus had

no real budget. The policy of the CDI project was to

systematically cover the hospital’s deficit as long as the

project had the necessary financial means to do so and

as long as this deficit remained within reasonable limits.

Obviously the room for financial manoeuvre shrank

continuously in the second half of the eighties and the

school were involved in routine hospital work from the

very beginning of their 4-year training curriculum.

Effectiveness and efficiency of the scheme: does it

facilitate access to the hospital for those patients who

need it?

The answer to this question is less clear-cut. It appears

first half of the nineties, due to the steep deterioration in

that insured persons have used the hospital services at a

the socio-economic situation (the decrease in prices paid

significantly higher rate than the uninsured. The

for locally grown coffee, traded on the international

admission rates in the insured population increased

market, meant a serious reduction in income for the

from 35.6 per thousand in 1988 to 49 per thousand in the

project) and to the reluctance of donors to fund

period April 1993 to March 1994 (x1 = 198; P < 0.001)

operating costs. Nevertheless it seems possible that the

whereas these rates hardly changed for uninsured

Bwamanda insurance scheme actually relieved the CDI

persons: 24.6 per thousand in 1988 and 2.4.9 Per

project from subsidizing the hospital to the same extent

thousand in 1993-94 (x* = °*I> P = °-75)«

as in the past. This may have led to displacement effects

ratio of hospital admission rates for insured compared

T988 the

where other activities within the CDI project, more in

with non-insured patients was almost 1.5; in 1993-94

need of financial resources, would have benefited from

this figure increased to a ratio of about 2. This ratio was

higher financial support. But as Zschock (1979) argues,

2.9 in the period 1993-94 when non-insured admissions

displacement is not necessarily a negative feature.

excluding patients covered by employer-organized

The financial data presented in the previous section

insurance schemes are concerned. If we consider higher

support the conclusion that Bwamanda hospital has

admission rates as an indicator of better accessibility to

become less dependent on external funding sources.

the hospital, then the answer seems straightforward,

This trend is clear, even though there probably are

even though the scheme may have selected precisely

problems with the accuracy and completeness of the

those families who were the higher hospital users even

financial data because of the complex accounting

before the insurance scheme was implemented.

procedures and mingling of funds within the

Bwamanda district, and because of the difficulty to

Hospital utilization is not, however, a goal in itself:

convert local into foreign currency values. It is

an increase in hospital utilization is a positive

phenomenon if it reflects the treatment of problems

reasonable to assume that this trend was maintained in

where the hospital’s know-how and technology are

the early nineties, since many fund-providers and aid

needed-. To what extent is this excess in hospital

organizations decided in the period 1990-91, for

utilization explained by an increase in ‘appropriate’

political reasons, to reduce or even to stop altogether

hospital utilization? Some of the arguments supporting

any further aid to Zaire.

Finally, it must be acknowledged that an annual

665

rationalization of resource use in the Bwamanda

hospital. For example, the trainees of the local nursing

the hypothesis that it is not due to a phenomenon of

moral hazard have already been pointed out. Firstly

hospital recurrent expenditure of USS 50 000, i.e. a mean

there is the mandatory referral of the patient by his

expenditure of USS 370 per inpatient bed, is very low

health centre (except for emergency situations), and

compared to similar hospitals in sub-Sahara Africa. In

secondly there is the system of small co-payments. It is

the 130-bed hospital in Hoima district in Uganda, the

possible that health centre nurses may now and then

mean expenditure per inpatient bed was USS 830

have been put under pressure by the patient to be

(unpublished data) and the Medicus Mundi

referred. If this did occur, however, there was a further

International survey of 59 NGO hospitals in sub-Sahara

control: on arrival at the hospital the patient would first

Africa indicated an average figure of approximately

be seen by the medical officer at the referral

USS 1 000 (Van Lerberghe et al. 1992). One explanation

consultation, who would decide whether admission was

for this low figure may be the extreme level of

appropriate or not.

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

VOLUME Z NO 7 PP 654-672 [ULY 1997

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

However, the fact that the excess in hospital

member, and all enjoy the same benefits in the event of

utilization by the insured population varies considerably

hospital admission, independently of the family’s socio

from one hospital department to the other indicates that

economic status and the other costs to the family of an

moral hazard is not by any means a homogenous

admission. These other costs are often substantial:

phenomenon. It may exist for some health problems and

indirect costs such as transport expenses, expenses for

less so, perhaps not at all, for others. The level of

food, expenses for the lodging of family members in

predictability of some health problems or events

Bwamanda town, etc. are often higher than the direct

requiring intervention at the hospital may be one of the

costs, i.e. the fee to be paid to the health care institution.

explanations. The distinction between predictable and

Two things need to be acknowledged at this stage: firstly

unpredictable health problems as an instrument for

the fact that in a rural environment like Bwamanda, the

assessing moral hazard has been applied in the

farther people live from the hospital, the higher are these

evaluation of the Masisi hospital insurance scheme in

indirect costs and the higher the opportunity cost of an

eastern Zaire (Noterman et al. 1995). The predictability

hypothesis may constitute a plausible explanation for

admission, and secondly the fact that the farther people

live from the hospital the lower their hospital utilization

the considerable increase in utilization of the hospital’s

(King 1966; KI00S1990). Hence members of the

maternity services, and perhaps even for the striking

insurance scheme who live far from rhe hospital, but pay

increase in utilization of surgical services. The latter

the same premium as members living close to it, actually

could be explained by a high proportion in this

subsidize the scheme. The premiums in the Bwamanda

incremental utilization of non-urgent surgery for

scheme are de facto regressive.

abdominal and inguinal hernias which are very

There is a need to study the design of systems which

prevalent health problems in the Bwamanda area. Our

aim to increase the solidarity basis of similar schemes.

data neither confirm nor disprove this hypothesis.

Such systems must not only be technically feasible, but

Further investigation is needed to elucidate this

financially affordable and socially acceptable (Gilson et

phenomenon of differences in hospital utilization.

al. 1995) as well. A system of sliding scales according to

The administrative costs of the scheme in the nineties

were between 5% and 10%, suggesting a relatively

distance from health centre to hospital was tried out in

Bwamanda in 1988 with the objective of tackling this

satisfactory level of administrative efficiency. These

problem. It was designed to channel benefits to a well-

costs are indeed far below the operating costs of social

defined target population, in this case people living far

insurance funds in other African countries (ILO 1988;

from the hospital. This is what Glewwe & van der Gaag

Gruat 1990; Shaw & Griffin 1995).

*s noc surprising to

(1988) call characteristic targeting, in this case according

find the highest proportion of administrative costs

to the geographical area where people live. In

(about 10%) in the years 1992 and 1994, when

Bwamanda the district team divided the health centre

subscription rates were lowest.

The data do not provide information on the effect of

network into 3 subgroups: a first group of health centres

the health insurance scheme on patients’ delay in seeking

second group (w = 8) 25-45 km away and a third group

(n = 7) located less than 25 km from the hospital, a

treatment. Comparison of admission rates between

(n = 7) more than 45 km from the hospital. The greater

insured and uninsured patients shows that insured

the distance from health centre to hospital, the lower the

individuals use the hospital more often, but does not

co-payment to be paid by the members when admitted

indicate whether patients actually come more timely.

to hospital (see Table 7). This system of characteristic

This is clearly one of the priorities for further study,

targeting did not have a positive impact on the hospital

since the problem of patient delay was one of the

admission rates of the more remote insured populations.

reasons which led to the development of hospital

A comparison of 1987 (without targeting) and 1988

insurance in the first place.

(with targeting) revealed that the rates remained similar

for groups 1 and 2, and that the rate for group 3 actually

fell in 1988 (see Figure 4).

Equity of the scheme?

In Bwamanda all families subscribing to the insurance

scheme pay the same premium per individual household

666

© 1997 Blackwell Science Ltd

In the following year it was decided to discontinue

this experiment with sliding scales because of the

absence of effect in terms of equity and to a lesser extent

VOLUME 2 NO 7 PP 654-672 JULY 1997

Tropical Medicine and International Health

B. Criel and G. Kegels

Table 7

Health insurance scheme for hospital care in Zaire

..

/ir» tgRR rhe average annual exchange rate was 187

Hospital fees in 1988 (Zaires). Sliding scales according to distance. (In 190 ,

_

Zaires for 1 USS)

Type of admission

Fee for uninsured

patients

Co-payment for

insured patients

from group 1*

Paediatrics

Internal medicine

Gynaecology

Maternity

Surgery I

Surgery II

Surgery III

Surgery IV

600

1800

1800

1800

1000

2500

3000

3500

350

350

—

200

500

600

700

120

__

Co-payment for

insured patients

from group 2**

Co-payment for

insured patients

from group 3***

60

180

180

—

100

250

300

30

100

100

350

50

120

150

180

Patients living in the catchment area of health centres situated* ar less then 25 km from the hospital,** between 25 and 45 km from

the hospital,*** at more than 45 km from the hospital.

because of the more complex management and control

1990). Differential premiums and fees for the poor,

procedures required (for instance, the origin of the

perhaps even exemption of payment, could be

admitted patients had to be systematically checked).

considered. Such a policy is called direct targeting, i.e. a

However, some members of the district management

system where the provision of benefits is limited to

team argued that the considerable social acceptability

individuals or households identified as belonging to the

the proposal had achieved among all 3 population

target group (Glewwe & van der Gaag 1988). Direct

groups constituted a strong enough case for continuing

targeting, in contrast to characteristic targeting, requires

the experiment. Moreover, the data did not permit

means-testing, i.e. a process where specific individuals

breaking down the number of admissions according to

are classified as eligible or ineligible for benefits (Willis

the nature and severity of the health problems for which

& Leighton 1995). Means-testing procedures could be

people were admitted.

The membership rate never exceeded two thirds of

tested in Bwamanda within the framework of the

hospital insurance scheme.

the total district population. A survey carried out in

1987 indicated that the very poor were represented to a

higher degree in the non-member population (Moens

Description of the environment in which the Bwamanda

scheme thrived

The authors’ hypothesis is that the relatively successful

development of the Bwamanda scheme, as well as its

viability, was possible because it took place in a

specific environment. However, the various constitutive